Covers following topics:

Origin, date, extent, characteristics,decline, survival and significance, art and architecture

Theory

The story of Harappa

- Very often, old buildings have a story to tell. Nearly a hundred and fifty years ago, when railway lines were being laid down for the first time in the Punjab, engineers stumbled upon the site of Harappa in present-day Pakistan.

- To them, it seemed like a mound that was a rich source of ready made, high quality bricks. So they carried off thousands of bricks from the walls of the old buildings of the city to build railway lines.

- Many buildings were completely destroyed. Then, about eighty years ago, archaeologists found the site, and realised that this was one of the oldest cities in the subcontinent.

- As this was the first city to be discovered, all other sites from where similar buildings (and other things) were found were described as Harappan.

- These cities developed about 4700 years ago.

What was special about these cities?

- Many of these cities were divided into two or more parts. Usually, the part to the west was smaller but higher. Archaeologists describe this as the citadel.

- Generally, the part to the east was larger but lower. This is called the lower town. Very often walls of baked brick were built around each part. The bricks were so well made that they have lasted for thousands of years. The bricks were laid in an interlocking pattern and that strong. made the walls In some cities, special buildings were constructed on the citadel. For example, in Mohenjodaro, a very special tank, which archaeologists call the Great Bath, was built in this area. This was lined with bricks, coated with plaster, and made water -tight with a layer of natural tar. There were steps leading down to it from two sides, while there were rooms on all sides. Water was probably brought in from a well, and drained out after use. Perhaps important people took a dip in this tank on special occasions. Other cities, such as Kalibangan and Lothal had fire altars, where sacrifices may have been performed. And some cities like Mohenjodaro, Harappa, and Lothal had elaborate store houses

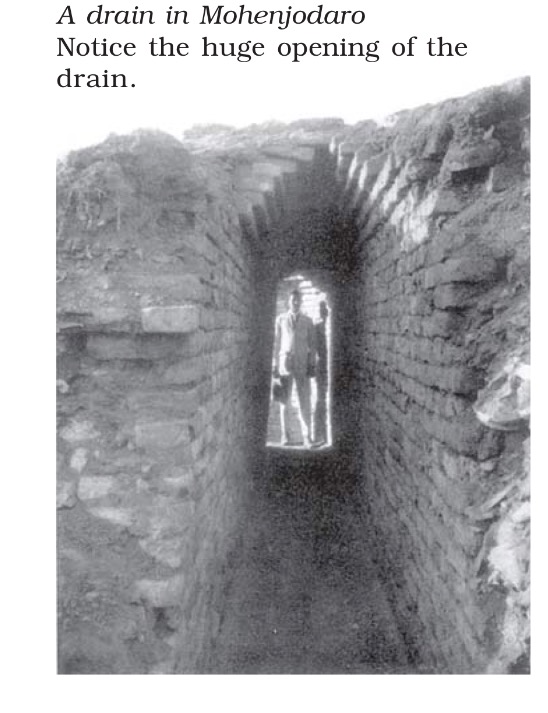

Houses, drains and streets

- Generally, houses were either one or two storeys high, with rooms built around a courtyard. Most houses had a separate bathing area, and some had wells to supply water. Many of these cities had covered drains. Each drain had a gentle slope so that water could flow through it. Very often, drains in houses were connected to those on the streets and smaller drains led into bigger ones. As the drains were covered, inspection holes were provided at intervals to clean them. All three — houses, drains and streets — were probably planned and built at the same time.

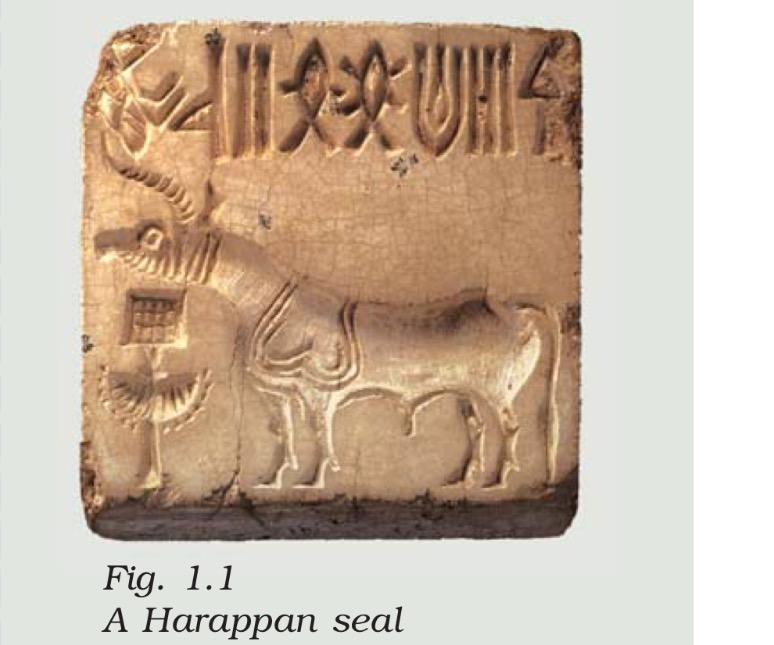

The Harappan seal

- It is possibly the most distinctive artefact of the Harappan or Indus valley civilisation.

- Made of a stone called steatite, seals like this one often contain animal motifs and signs from a script that remains undeciphered.

- Yet we know a great deal about the lives of the people who lived in the region from what they left behind – their houses, pots, ornaments, tools and seals – in other words, from archaeological evidence.

Let us see what we know about the Harappan civilisation, and how we know about it.Of course, there are some aspects of the civilisation that are as yet unknown and may even remain so.

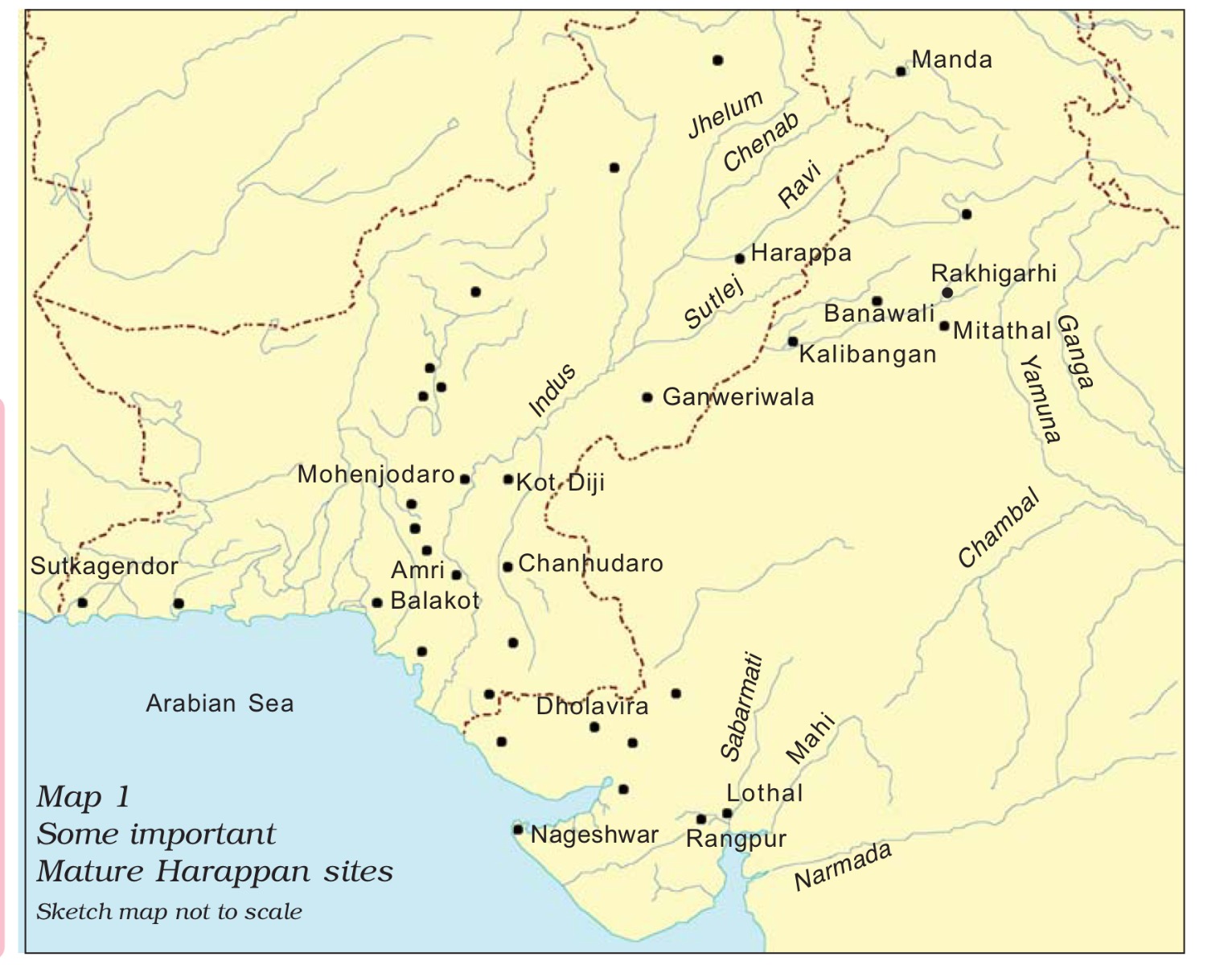

- The Indus valley civilisation is also called the Harappan culture. Archaeologists use the term “culture” for a group of objects, distinctive in style, that are usually found together within a specific geographical area and period of time. In the case of the Harappan culture, these distinctive objects include seals, beads, weights, stone blade and even baked bricks. These objects were found from areas as far apart as Afghanistan, Jammu, Baluchistan (Pakistan) and Gujarat.

- Named after Harappa, the first site where this unique culture was discovered, the civilisation is dated between c. 2600 and 1900 BCE.

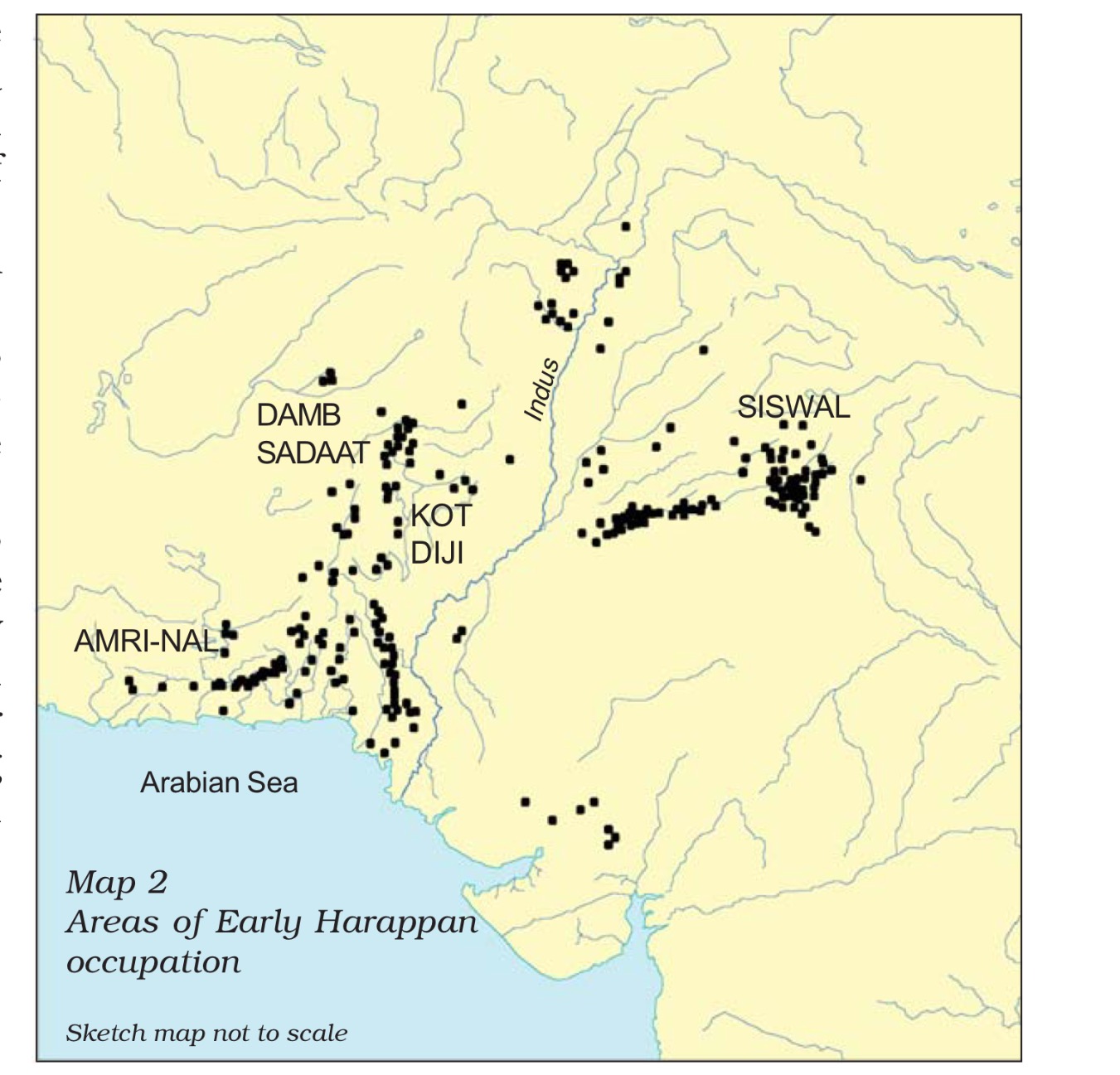

- There were earlier and later cultures, often called Early Harappan and Late Harappan, in the same area.

- The Harappan civilisation is sometimes called the Mature Harappan culture to distinguish it from these cultures.

Beginnings

- There were several archaeological cultures in the region prior to the Mature Harappan.

- These cultures were associated with distinctive pottery, evidence of agriculture and pastoralism, and some crafts.

- Settlements were generally small, and there were virtually no large buildings.

- It appears that there was a break between the Early Harappan and the Harappan civilisation, evident from large-scale burning at some sites, as well as the abandonment of certain settlements.

Subsistence Strategies

- Mature Harappan culture developed in some of the areas occupied by the Early Harappan cultures. These cultures also shared certain common elements including subsistence strategies.

- The Harappans ate a wide range of plant and animal products, including fish.

- Archaeologists have been able to reconstruct dietary practices from finds of charred grains and seeds. These are studied by archaeo-botanists, who are specialists in ancient plant remains.

- Grains found at Harappan sites include wheat, barley, lentil, chickpea and sesame.

- Millets are found from sites in Gujarat. Finds of rice are relatively rare.

- Animal bones found at Harappan sites include those of cattle, sheep, goat, buffalo and pig. Studies done by archaeo-zoologists or zoo- archaeologists indicate that these animals were domesticated.

- Bones of wild species such as boar, deer and gharial are also found. We do not know whether the Harappans hunted these animals themselves or obtained meat from other hunting communities.

- Bones of fish and fowl are also found.

Agricultural technologies

- While the prevalence of agriculture is indicated by finds of grain, it is more difficult to reconstruct actual agricultural practices. Were seeds broadcast (scattered) on ploughed lands?

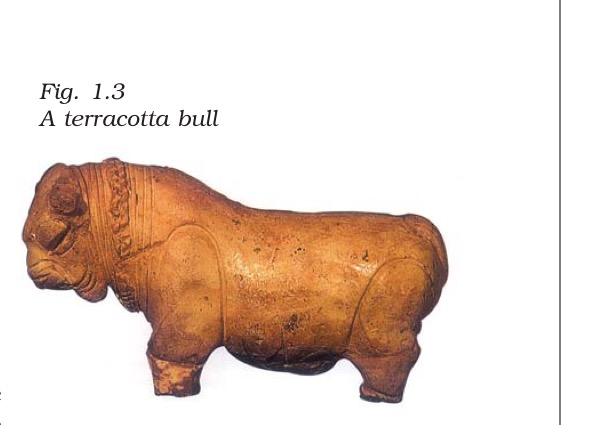

- Representations on seals and terracotta sculpture indicate that the bull was known, and archaeologists extrapolate from this that oxen were used for ploughing.

- Moreover, terracotta models of the plough have been found at sites in Cholistan and at Banawali (Haryana).

- Archaeologists have also found evidence of a ploughed field at Kalibangan (Rajasthan), associated with Early Harappan levels. The field had two sets of furrows at right angles to each other, suggesting that two different crops were grown together.

- Archaeologists have also tried to identify the tools used for harvesting. Did the Harappans use stone blades set in wooden handles or did they use metal tools?

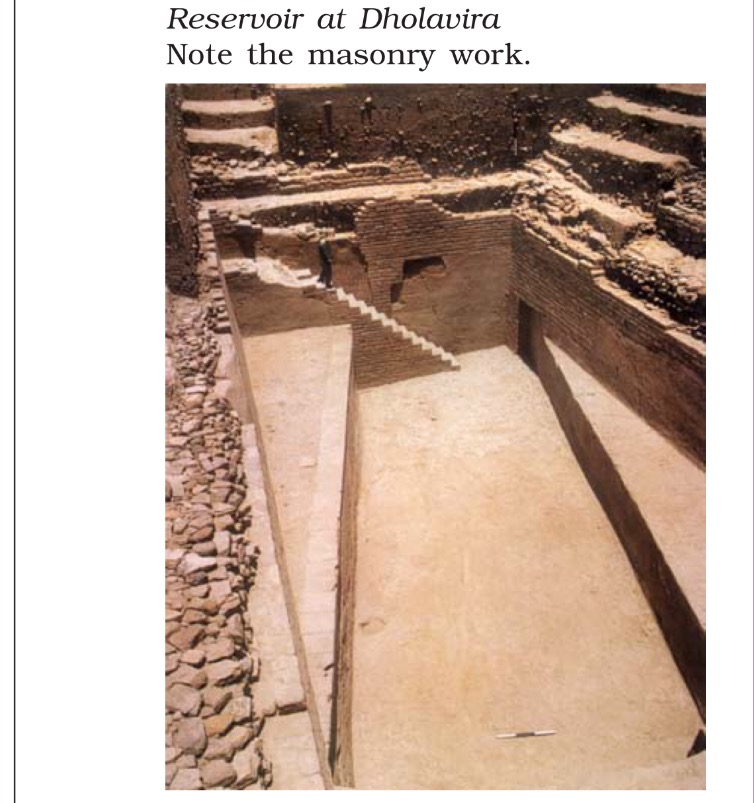

- Most Harappan sites are located in semi-arid lands, where irrigation was probably required for agriculture.

- Traces of canals have been found at the Harappan site of Shortughai in Afghanistan, but not in Punjab or Sind. It is possible that ancient canals silted up long ago.

- It is also likely that water drawn from wells was used for irrigation. Besides, water reservoirs found in Dholavira (Gujarat) may have been used to store water for agriculture.

The plight of Harappa

Although Harappa was the first site to be discovered, it was badly destroyed by brick robbers. As early as 1875, Alexander Cunningham, the first Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), often called the father of Indian archaeology, noted that the amount of brick taken from the ancient site was enough to lay bricks for “about 100 miles” of the railway line between Lahore and Multan. Thus, many of the ancient structures at the site were damaged. In contrast, Mohenjodaro was far better preserved.

Life in the city

- A Harappan city was a very busy place. There were people who planned the construction of special buildings in the city. These were probably the rulers. It is likely that the rulers sent people to distant lands to get metal, precious stones, and other things that they wanted.

- They may have kept the most valuable objects, such as ornaments of gold and silver, or beautiful beads, for themselves. And there were scribes, people who knew how to write, who helped prepare the seals, and perhaps wrote on other materials that have not survived.

- Besides, there were men and women, crafts persons, making all kinds of things — either in their own homes, or in special workshops. People were travelling to distant lands or returning with raw materials and, perhaps, stories. Many terracotta toys have been found and a long time ago children must have played with these.

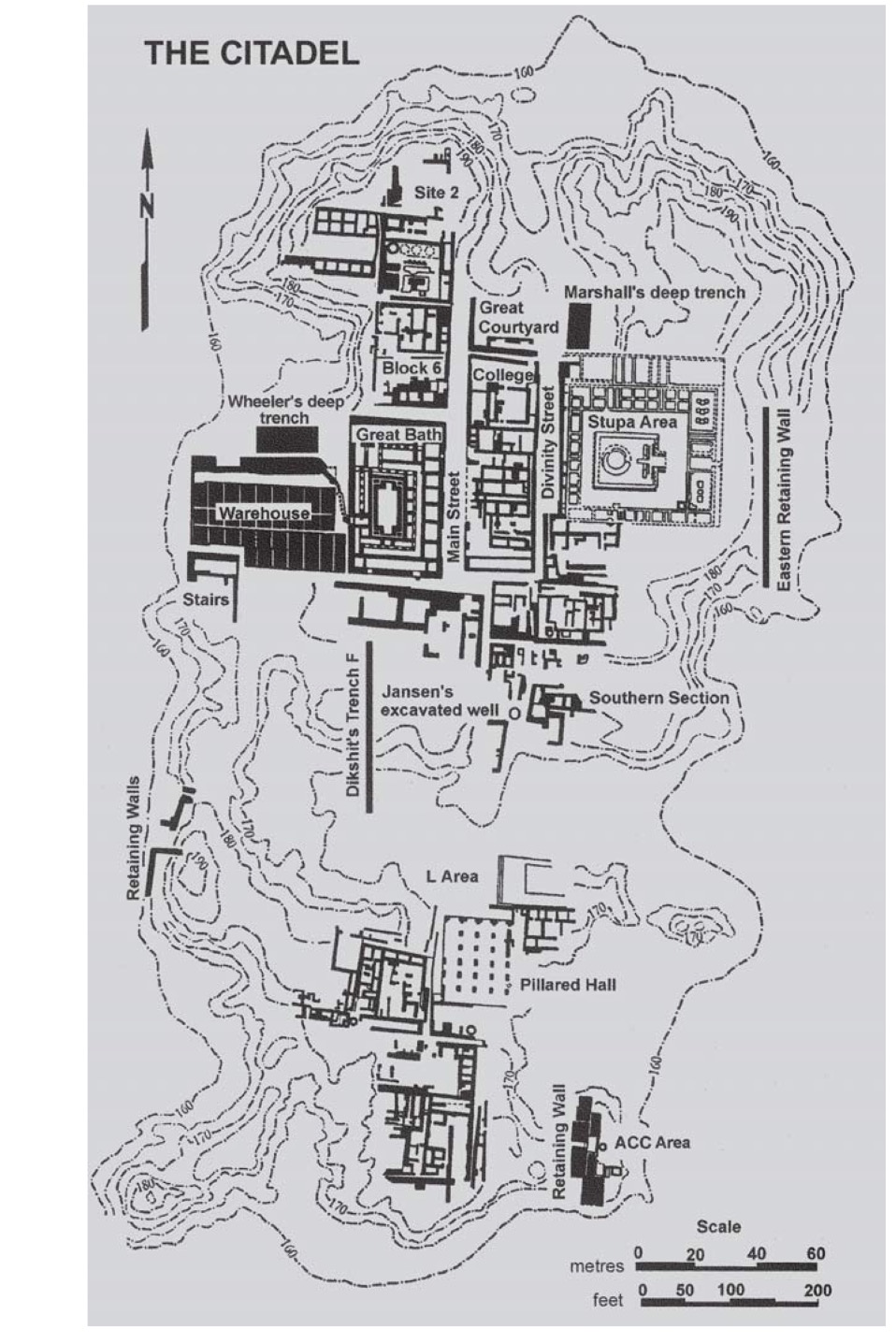

Mohenjodaro A Planned Urban Centre

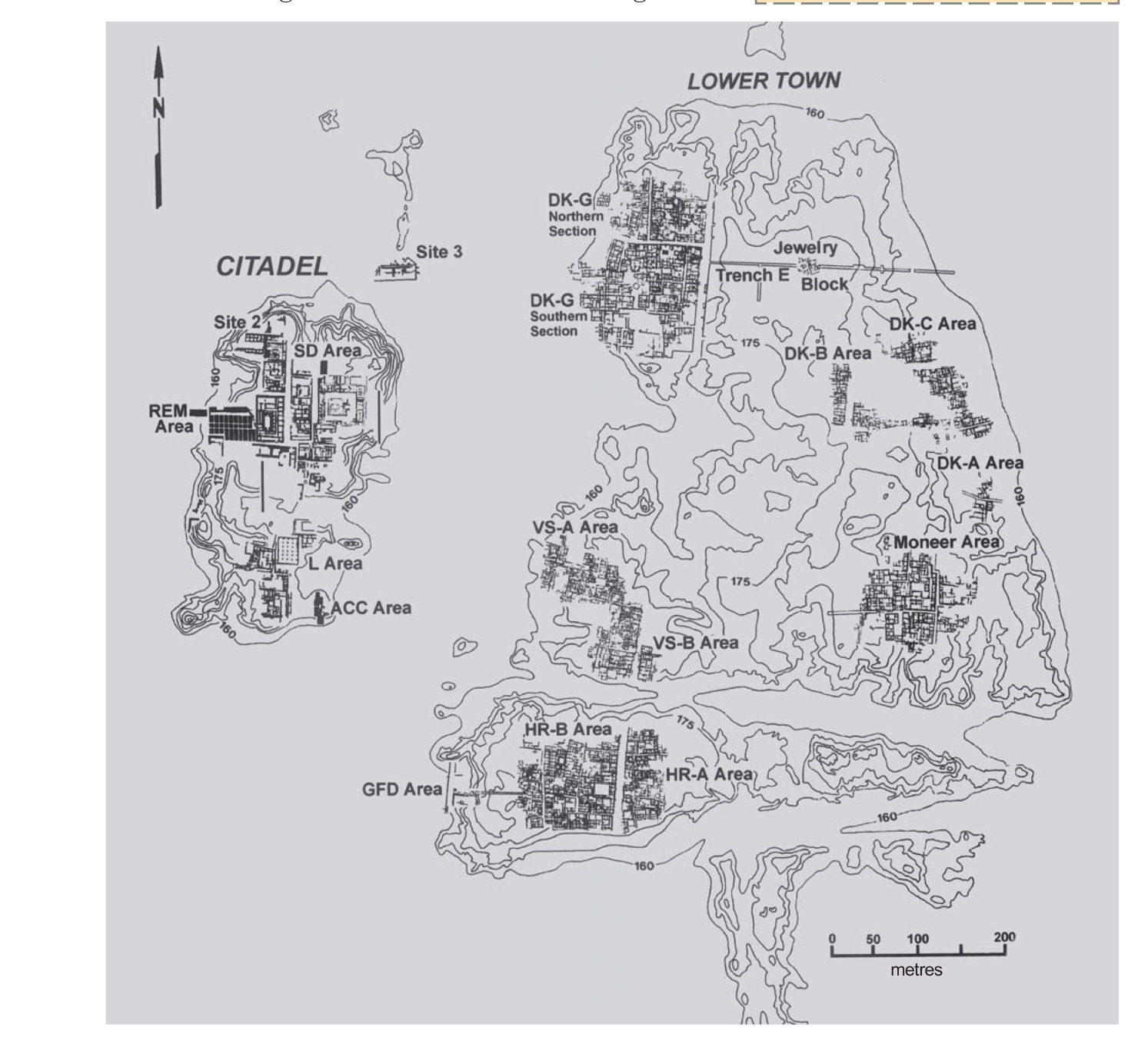

- Perhaps the most unique feature of the Harappan civilisation was the development of urban centres. Let us look at one such centre, Mohenjodaro, more closely.

- Although Mohenjodaro is the most well-known site, the first site to be discovered was Harappa.

- The settlement is divided into two sections, one smaller but higher and the other much larger but lower. Archaeologists designate these as the Citadel and the Lower Town respectively.

- The Citadel owes its height to the fact that buildings were constructed on mud brick platforms. It was walled, which meant that it was physically separated from the Lower Town.

- The Lower Town was also walled. Several buildings were built on platforms, which served as foundations. It has been calculated that if one labourer moved roughly a cubic metre of earth daily, just to put the foundations in place it would have required four million person-days, in other words, mobilising labour on a very large scale.

- Consider something else. Once the platforms were in place, all building activity within the city was restricted to a fixed area on the platforms. So it seems that the settlement was first planned and then implemented accordingly.

- Other signs of planning include bricks, which, whether sun-dried or baked, were of a standardised ratio, where the length and breadth were four times and twice the height respectively. Such bricks were used at all Harappan settlements.

Laying out drains

- One of the most distinctive features of Harappan cities was the carefully planned drainage system.

- If you look at the plan of the Lower Town you will notice that roads and streets were laid out along an approximate “grid” pattern, intersecting at right angles.

- It seems that streets with drains were laid out first and then houses built along them.

- If domestic waste water had to flow into the street drains, every house needed to have at least one wall along a street.

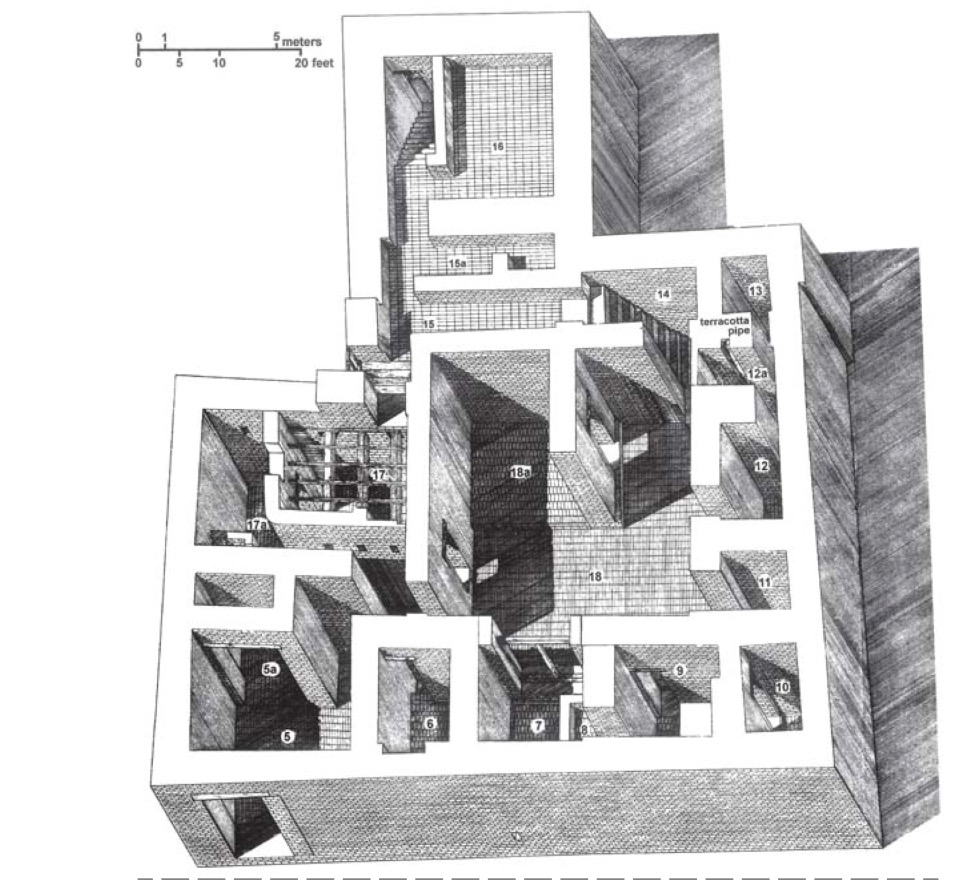

Domestic architecture

- The Lower Town at Mohenjodaro provides examples of residential buildings.

- Many were centred on a courtyard, with rooms on all sides. The courtyard was probably the centre of activities such as cooking and weaving, particularly during hot and dry weather.

- What is also interesting is an apparent concern for privacy: there are no windows in the walls along the ground level. Besides, the main entrance does not give a direct view of the interior or the courtyard.

- Every house had its own bathroom paved with bricks, with drains connected through the wall to the street drains.

- Some houses have remains of staircases to reach a second storey or the roof.

- Many houses had wells, often in a room that could be reached from the outside and perhaps used by passers-by. Scholars have estimated that the total number of wells in Mohenjodaro was about 700

The Citadel

- It is on the Citadel that we find evidence of structures that were probably used for special public purposes.

- These include the warehouse – a massive structure of which the lower brick portions remain, while the upper portions, probably of wood, decayed long ago – and the Great Bath.

- The Great Bath was a large rectangular tank in a courtyard surrounded by a corridor on all four sides. There were two flights of steps on the north and south leading into the tank, which was made watertight by setting bricks on edge and using a mortar of gypsum. There were rooms on three sides, in one of which was a large well. Water from the tank flowed into a huge drain. Across a lane to the north lay a smaller building with eight bathrooms, four on each side of a corridor, with drains from each bathroom connecting to a drain that ran along the corridor. The uniqueness of the structure, as well as the context in which it was found (the Citadel, with several distinctive buildings), has led scholars to suggest that it was meant for some kind of a special ritual bath.

- While most Harappan settlements have a small high western part and a larger lower eastern section, there are variations. At sites such as Dholavira and Lothal (Gujarat), the entire settlement was fortified, and sections within the town were also separated by walls. The Citadel within Lothal was not walled off, but was built at a height.

Tracking Social Differences

Burials

- Archaeologists generally use certain strategies to find out whether there were social or economic differences amongst people living within a particular culture. These include studying burials.

- You are probably familiar with the massive pyramids of Egypt, some of which were contemporaneous with the Harappan civilisation. Many of these pyramids were royal burials, where enormous quantities of wealth was buried.

- At burials in Harappan sites the dead were generally laid in pits.

- Sometimes, there were differences in the way the burial pit was made – in some instances, the hollowed-out spaces were lined with bricks. Could these variations be an indication of social differences? We are not sure.

- Some graves contain pottery and ornaments, perhaps indicating a belief that these could be used in the afterlife.

- Jewellery has been found in burials of both men and women. In fact, in the excavations at the cemetery in Harappa in the mid-1980s, an ornament consisting of three shell rings, a jasper (a kind of semi-precious stone) bead and hundreds of micro beads was found near the skull of a male.

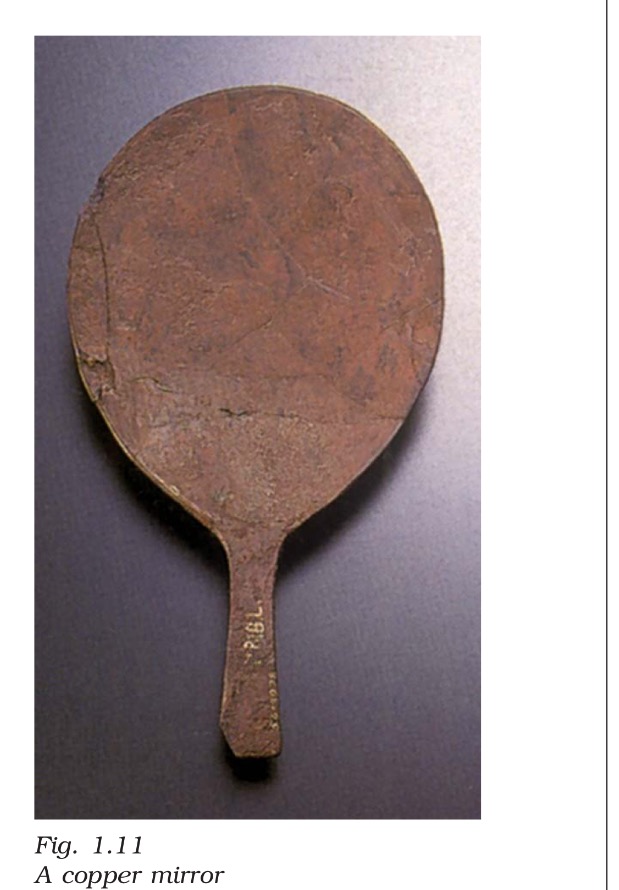

- In some instances the dead were buried with copper mirrors.

- But on the whole, it appears that the Harappans did not believe in burying precious things with the dead.

Looking for “luxuries”

- Another strategy to identify social differences is to study artefacts, which archaeologists broadly classify as utilitarian and luxuries.

- The first category includes objects of daily use made fairly easily out of ordinary materials such as stone or clay. These include querns, pottery, needles, flesh-rubbers (body scrubbers), etc., and are usually found distributed throughout settlements.

- Archaeologists assume objects were luxuries if they are rare or made from costly, non-local materials or with complicated technologies.

- Thus, little pots of faience (a material made of ground sand or silica mixed with colour and a gum and then fired) were probably considered precious because they were difficult to make.

- The situation becomes more complicated when we find what seem to be articles of daily use, such as spindle whorls made of rare materials such as faience. Do we classify these as utilitarian or luxuries? If we study the distribution of such artefacts, we find that rare objects made of valuable materials are generally concentrated in large settlements like Mohenjodaro and Harappa and are rarely found in the smaller settlements.

- For example, miniature pots of faience, perhaps used as perfume bottles, are found mostly in Mohenjodaro and Harappa, and there are none from small settlements like Kalibangan. Gold too was rare, and as at present, probably precious – all the gold jewellery found at Harappan sites was recovered from hoards.

New crafts in the city

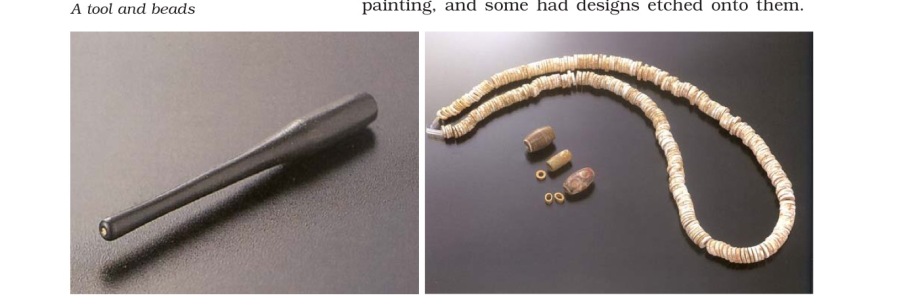

Let us look at some of the objects that were made and found in Harappan cities. Most of the things that have been found by archaeologists are made of stone, shell and metal, including copper, bronze, gold and silver. Copper and bronze were used to make tools, weapons, ornaments and vessels. Gold and silver were used to make ornaments and vessels. Perhaps the most striking finds are those of beads, weights, and blades. The Harappans also made seals out of stone. These are generally rectangular and usually have an animal carved on them. The Harappans also made pots with beautiful black designs. Cotton was probably grown at Mehrgarh from about 7000 years ago. Actual pieces of cloth were found attached to the lid of a silver vase and some copper objects at Mohenjodaro. Archaeologists have also found spindle whorls, made of terracotta and faience. These were used to spin thread. Many of the things that were produced were probably the work of specialists. A specialist is a person who is trained to do only one kind of work, for example, cutting stone, or polishing beads, or carving seals. We do not know whether only men were specialists or only women were specialists. Perhaps some women and men may have been specialists.

Finding Out About Craft Production

- Locate Chanhudaro on Map. This is a tiny settlement (less than 7 hectares) as compared to Mohenjodaro (125 hectares), almost exclusively devoted to craft production, including bead-making, shell-cutting, metal-working, seal-making and weight-making.

- The variety of materials used to make beads is remarkable: stones like carnelian (of a beautiful red colour), jasper, crystal, quartz and steatite; metals like copper, bronze and gold; and shell, faience and terracotta or burnt clay.

- Some beads were made of two or more stones, cemented together, some of stone with gold caps. The shapes were numerous – disc- shaped, cylindrical, spherical, barrel-shaped, segmented.

- Some were decorated by incising or painting, and some had designs etched onto them.

- Techniques for making beads differed according to the material. Steatite, a very soft stone, was easily worked. Some beads were moulded out of a paste made with steatite powder. This permitted making a variety of shapes, unlike the geometrical forms made out of harder stones.

- How the steatite micro bead was made remains a puzzle for archaeologists studying ancient technology.

- Archaeologists’ experiments have revealed that the red colour of carnelian was obtained by firing the yellowish raw material and beads at various stages of production.

- Nodules were chipped into rough shapes, and then finely flaked into the final form. Grinding, polishing and drilling completed the process. Specialised drills have been found at Chanhudaro, Lothal and more recently at Dholavira.

- If you locate Nageshwar and Balakot on Map, you will notice that both settlements are near the coast. These were specialised centres for making shell objects – including bangles, ladles and inlay – which were taken to other settlements.

- Similarly, it is likely that finished products (such as beads) from Chanhudaro and Lothal were taken to the large urban centres such as Mohenjodaro and Harappa.

Identifying centres of production

- In order to identify centres of craft production, archaeologists usually look for the following: raw material such as stone nodules, whole shells, copper ore; tools; unfinished objects; rejects and waste material.

- In fact, waste is one of the best indicators of craft work. For instance, if shell or stone is cut to make objects, then pieces of these materials will be discarded as waste at the place of production.

- Sometimes, larger waste pieces were used up to make smaller objects, but minuscule bits were usually left in the work area.

- These traces suggest that apart from small, specialised centres, craft production was also undertaken in large cities such as Mohenjodaro and Harappa.

In search of raw materials

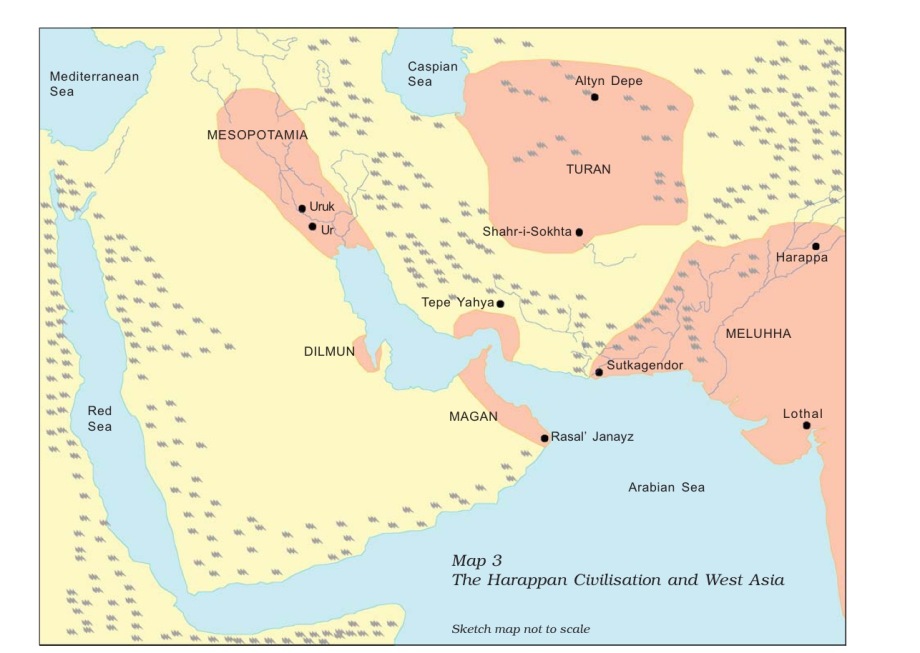

Raw materials are substances that are either found naturally (such as wood, or ores of metals) or produced by farmers or herders. These are then processed to produce finished goods. For example, cotton, produced by farmers, is a raw material that may be processed to make cloth. While some of the raw materials that the Harappans used were available locally, many items such as copper, tin, gold, silver and precious stones had to be brought from distant places. The Harappans probably got copper from present-day Rajasthan, and even from Oman in West Asia. Tin, which was mixed with copper to produce bronze, may have been brought from present-day Afghanistan and Iran. Gold could have come all the way from present-day Karnataka, and precious stones from present-day Gujarat, Iran and Afghanistan.

Strategies for Procuring Materials

- As is obvious, a variety of materials was used for craft production. While some such as clay were locally available, many such as stone, timber and metal had to be procured from outside the alluvial plain.

- Terracotta toy models of bullock carts suggest that this was one important means of transporting goods and people across land routes. Riverine routes along the Indus and its tributaries, as well as coastal routes were also probably used.

Materials from the subcontinent and beyond

- The Harappans procured materials for craft production in various ways. For instance, they established settlements such as Nageshwar and Balakot in areas where shell was available.

- Other such sites were Shortughai, in far-off Afghanistan, near the best source of lapis lazuli, a blue stone that was apparently very highly valued, and Lothal which was near sources of carnelian (from Bharuch in Gujarat), steatite (from south Rajasthan and north Gujarat) and metal (from Rajasthan).

- Another strategy for procuring raw materials may have been to send expeditions to areas such as the Khetri region of Rajasthan (for copper) and south India (for gold).

- These expeditions established communication with local communities. Occasional finds of Harappan artefacts such as steatite micro beads in these areas are indications of such contact.

- There is evidence in the Khetri area for what archaeologists call the Ganeshwar-Jodhpura culture, with its distinctive non-Harappan pottery and an unusual wealth of copper objects.

- It is possible that the inhabitants of this region supplied copper to the Harappans.

Contact with distant lands

- Recent archaeological finds suggest that copper was also probably brought from Oman, on the south- eastern tip of the Arabian peninsula. Chemical analyses have shown that both the Omani copper and Harappan artefacts have traces of nickel, suggesting a common origin.

- There are other traces of contact as well. A distinctive type of vessel, a large Harappan jar coated with a thick layer of black clay has been found at Omani sites. Such thick coatings prevent the percolation of liquids. We do not know what was carried in these vessels, but it is possible that the Harappans exchanged the contents of these vessels for Omani copper.

- Mesopotamian texts datable to the third millennium BCE refer to copper coming from a region called Magan, perhaps a name for Oman, and interestingly enough copper found at Mesopotamian sites also contains traces of nickel.

- Other archaeological finds suggestive of long- distance contacts include Harappan seals, weights, dice and beads. In this context, it is worth noting that Mesopotamian texts mention contact with regions named Dilmun (probably the island of Bahrain), Magan and Meluhha, possibly the Harappan region.

- They mention the products from Meluhha: carnelian, lapis lazuli, copper, gold, and varieties of wood. A Mesopotamian myth says of Meluhha: “May your bird be the haja-bird, may its call be heard in the royal palace.” Some archaeologists think the haja-bird was the peacock. Did it get this name from its call? It is likely that communication with Oman, Bahrain or Mesopotamia was by sea.

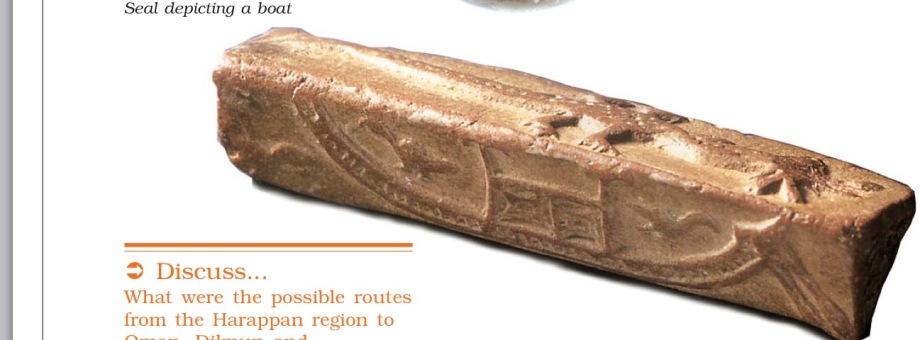

- Mesopotamian texts refer to Meluhha as a land of seafarers. Besides, we find depictions of ships and boats on seals.

Seals, Script, Weights

Seals and sealings

- Seals and sealings were used to facilitate long- distance communication.

- Imagine a bag of goods being sent from one place to another. Its mouth was tied with rope and on the knot was affixed some wet clay on which one or more seals were pressed, leaving an impression. If the bag reached with its sealing intact, it meant that it had not been tampered with.

- The sealing also conveyed the identity of the sender.

An enigmatic script

- Harappan seals usually have a line of writing, probably containing the name and title of the owner.

- Scholars have also suggested that the motif (generally an animal) conveyed a meaning to those who could not read.

- Most inscriptions are short, the longest containing about 26 signs.

- Although the script remains undeciphered to date, it was evidently not alphabetical (where each sign stands for a vowel or a consonant) as it has just too many signs – somewhere between 375 and 400.

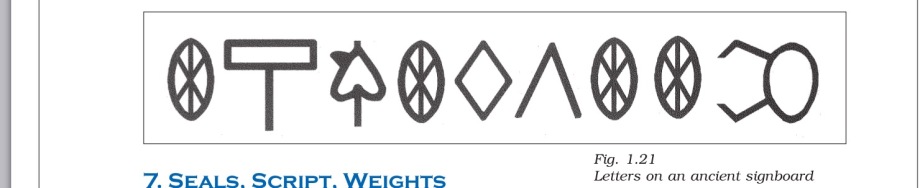

- It is apparent that the script was written from right to left as some seals show a wider spacing on the right and cramping on the left, as if the engraver began working from the right and then ran out of space.

- Consider the variety of objects on which writing has been found: seals, copper tools, rims of jars, copper and terracotta tablets, jewellery, bone rods, even an ancient signboard! Remember, there may have been writing on perishable materials too. Could this mean that literacy was widespread?

Weights

- Exchanges were regulated by a precise system of weights, usually made of a stone called chert and generally cubical, with no markings.

- The lower denominations of weights were binary (1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, etc. up to 12,800), while the higher denominations followed the decimal system.

- The smaller weights were probably used for weighing jewellery and beads. Metal scale-pans have also been found.

Food for people in the cities

While many people lived in the cities, others living in the countryside grew crops and reared animals. These farmers and herders supplied food to crafts persons, scribes and rulers in the cities. We know from remains of plants that the Harappans grew wheat, barley, pulses, peas, rice, sesame, linseed and mustard. A new tool, the plough, was used to dig the earth for turning the soil and planting seeds. While real ploughs, which were probably made of wood, have not survived, toy models have been found. As this region does not receive heavy rainfall, some form of irrigation may have been used. This means that water was stored and supplied to the fields when the plants were growing. The Harappans reared cattle, sheep, goat and buffalo. Water and pastures were available around settlements. However, in the dry summer months large herds of animals were probably taken to greater distances in search of grass and water. They also collected fruits like ber, caught fish and hunted wild animals like the antelope.

Ancient Authority

- There are indications of complex decisions being taken and implemented in Harappan society. Take for instance, the extraordinary uniformity of Harappan artefacts as evident in pottery , seals, weights and bricks.

- Notably, bricks, though obviously not produced in any single centre, were of a uniform ratio throughout the region, from Jammu to Gujarat.

- We have also seen that settlements were strategically set up in specific locations for various reasons. Besides, labour was mobilised for making bricks and for the construction of massive walls and platforms. Who organised these activities?

Palaces and kings

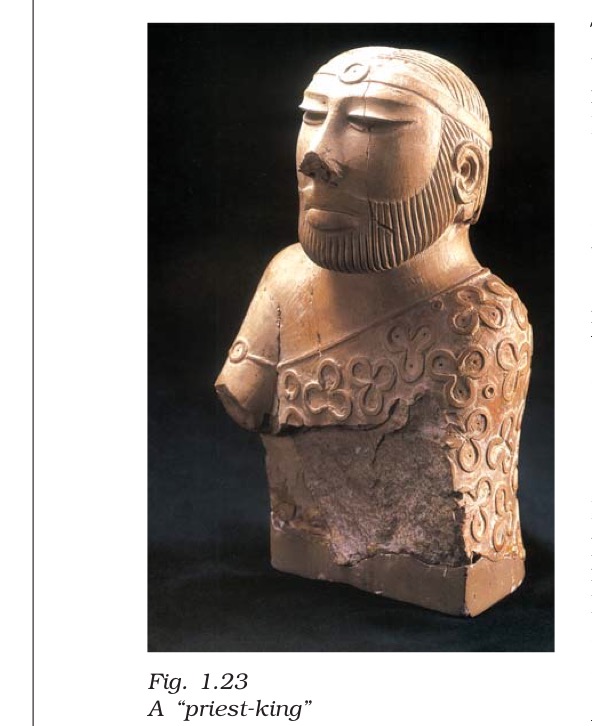

- If we look for a centre of power or for depictions of people in power, archaeological records provide no immediate answers. A large building found at Mohenjodaro was labelled as a palace by archaeologists but no spectacular finds were associated with it.

- A stone statue was labelled and continues to be known as the “priest-king”. This is because archaeologists were familiar with Mesopotamian history and its “priest-kings” and have found parallels in the Indus region.

- But as we will see, the ritual practices of the Harappan civilisation are not well understood yet nor are there any means of knowing whether those who performed them also held political power.

- Some archaeologists are of the opinion that Harappan society had no rulers, and that everybody enjoyed equal status.

- Others feel there was no single ruler but several, that Mohenjodaro had a separate ruler, Harappa another, and so forth.

- Yet others argue that there was a single state, given the similarity in artefacts, the evidence for planned settlements, the standardised ratio of brick size, and the establishment of settlements near sources of raw material.

- As of now, the last theory seems the most plausible, as it is unlikely that entire communities could have collectively made and implemented such complex decisions.

Around 3900 years ago we find the beginning of a major change. People stopped living in many of the cities. Writing, seals and weights were no longer used. Raw materials brought from long distances became rare. In Mohenjodaro, we find that garbage piled up on the streets, the drainage system broke down, and new, less impressive houses were built, even over the streets. Why did all this happen? We are not sure. Some scholars suggest that the rivers dried up. Others suggest that there was deforestation. This could have happened because fuel was required for baking bricks, and for smelting copper ores. Besides, grazing by large herds of cattle, sheep and goat may have destroyed the green cover. In some areas there were floods. But none of these reasons can explain the end of all the cities. Flooding, or a river drying up would have had an effect in only some areas. It appears as if the rulers lost control. In any case, the effects of the change are quite clear. Sites in Sind and west Punjab (present-day Pakistan) were abandoned, while many people moved into newer, smaller settlements to the east and the south. New cities emerged about 1400 years later.

The End of the Civilisation

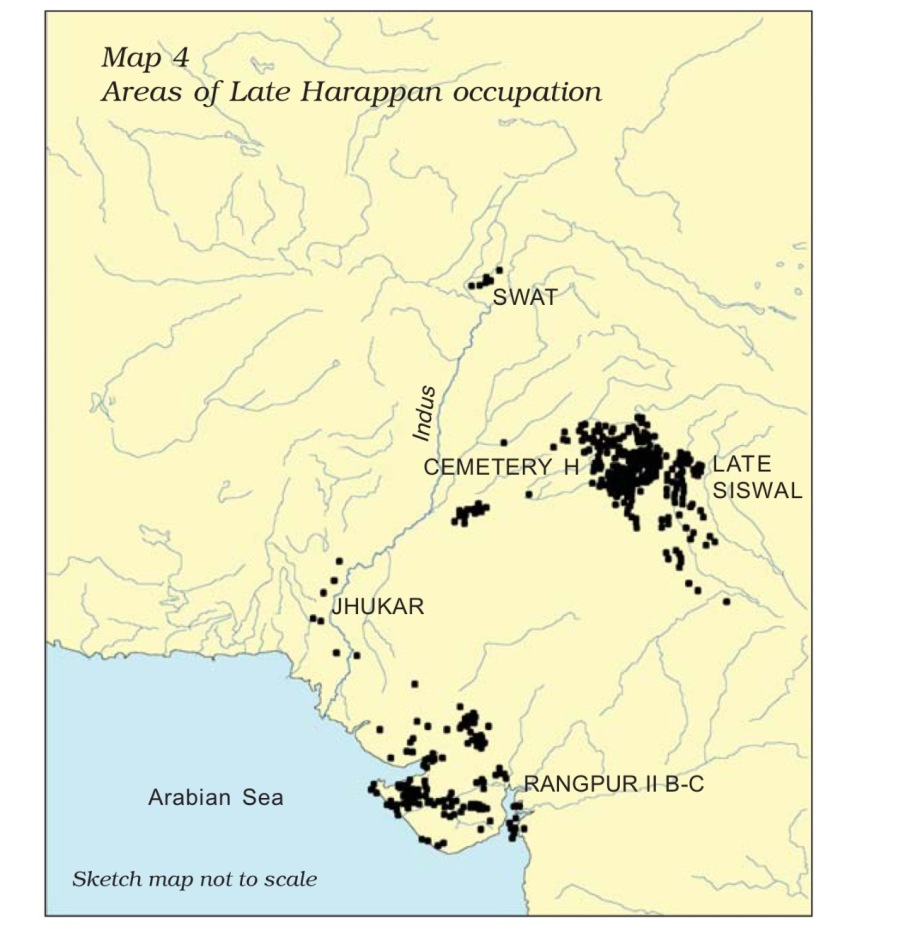

- There is evidence that by c. 1800 BCE most of the Mature Harappan sites in regions such as Cholistan had been abandoned. Simultaneously, there was an expansion of population into new settlements in Gujarat, Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh.

- In the few Harappan sites that continued to be occupied after 1900 BCE there appears to have been a transformation of material culture, marked by the disappearance of the distinctive artefacts of the civilisation – weights, seals, special beads. Writing, long-distance trade, and craft specialisation also disappeared.

- In general, far fewer materials were used to make far fewer things. House construction techniques deteriorated and large public structures were no longer produced. Overall, artefacts and settlements indicate a rural way of life in what are called “Late Harappan” or “successor cultures”.

- What brought about these changes? Several explanations have been put forward. These range from climatic change, deforestation, excessive floods, the shifting and/or drying up of rivers, to overuse of the landscape.

- Some of these “causes” may hold for certain settlements, but they do not explain the collapse of the entire civilisation.

- It appears that a strong unifying element, perhaps the Harappan state, came to an end. This is evidenced by the disappearance of seals, the script, distinctive beads and pottery, the shift from a standardised weight system to the use of local weights; and the decline and abandonment of cities. The subcontinent would have to wait for over a millennium for new cities to develop in a completely different region.

Discovering the Harappan Civilisation

- So far, we have examined facets of the Harappan civilisation in the context of how archaeologists have used evidence from material remains to piece together parts of a fascinating history.

- However, there is another story as well – about how archaeologists “discovered” the civilisation. When Harappan cities fell into ruin, people gradually forgot all about them. When men and women began living in the area millennia later, they did not know what to make of the strange artefacts that occasionally surfaced, washed by floods or exposed by soil erosion, or turned up while ploughing a field, or digging for treasure.

Cunningham’s confusion

- When Cunningham, the first Director-General of the ASI, began archaeological excavations in the mid- nineteenth century, archaeologists preferred to use the written word (texts and inscriptions) as a guide to investigations.

- In fact, Cunningham’s main interest was in the archaeology of the Early Historic (c. sixth century BCE-fourth century CE) and later periods. He used the accounts left by Chinese Buddhist pilgrims who had visited the subcontinent between the fourth and seventh centuries CE to locate early settlements.

- Cunningham also collected, documented and translated inscriptions found during his surveys. When he excavated sites he tended to recover artefacts that he thought had cultural value.

- A site like Harappa, which was not part of the itinerary of the Chinese pilgrims and was not known as an Early Historic city, did not fit very neatly within his framework of investigation. So, although Harappan artefacts were found fairly often during the nineteenth century and some of these reached Cunningham, he did not realise how old these were.

- A Harappan seal was given to Cunningham by an Englishman. He noted the object, but unsuccessfully tried to place it within the time-frame with which he was familiar.

- This was because he, like many others, thought that Indian history began with the first cities in the Ganga valley. Given his specific focus, it is not surprising that he missed the significance of Harappa.

A closer look — Harappan towns in Gujarat

- The city of Dholavira was located on Khadir Beyt in the Rann of Kutch, where there was fresh water and fertile soil.

- Unlike some of the other Harappan cities, which were divided into two parts, Dholavira was divided into three parts, and each part was surrounded with massive stone walls, with entrances through gateways.

- There was also a large open area in the settlement, where public ceremonies could be held.

- Other finds include large letters of the Harappan script that were carved out of white stone and perhaps inlaid in wood. This is a unique find as generally Harappan writing has been found on small objects such as seals.

- The city of Lothal stood beside a tributary of the Sabarmati, in Gujarat, close to the Gulf of Khambat. It was situated near areas where raw materials such as semi-precious stones were easily available.

- This was an important centre for making objects out of stone, shell and metal. There was also a store house in the city. Many seals and sealings (the impression of seals on clay) were found in this storehouse.

- A building that was found here was probably a workshop for making beads: pieces of stone, half made beads, tools for bead making, and finished beads have all been found here.

A new old civilisation

- Subsequently, seals were discovered at Harappa by archaeologists such as Daya Ram Sahni in the early decades of the twentieth century, in layers that were definitely much older than Early Historic levels. It was then that their significance began to be realised.

- Another archaeologist, Rakhal Das Banerji found similar seals at Mohenjodaro, leading to the conjecture that these sites were part of a single archaeological culture.

- Based on these finds, in 1924, John Marshall, Director -General of the ASI, announced the discovery of a new civilisation in the Indus valley to the world. As S.N. Roy noted in The Story of Indian Archaeology, “Marshall left India three thousand years older than he had found her.”

- This was because similar, till-then-unidentified seals were found at excavations at Mesopotamian sites. It was then that the world knew not only of a new civilisation, but also of one contemporaneous with Mesopotamia.

- In fact, John Marshall’s stint as Director-General of the ASI marked a major change in Indian archaeology. He was the first professional archaeologist to work in India, and brought his experience of working in Greece and Crete to the field.

- More importantly, though like Cunningham he too was interested in spectacular finds, he was equally keen to look for patterns of everyday life. Marshall tended to excavate along regular horizontal units, measured uniformly throughout the mound, ignoring the stratigraphy of the site.

- This meant that all the artefacts recovered from the same unit were grouped together, even if they were found at different stratigraphic layers. As a result, valuable information about the context of these finds was irretrievably lost.

New techniques and questions

- It was R.E.M. Wheeler, after he took over as Director- General of the ASI in 1944, who rectified this problem.

- Wheeler recognised that it was necessary to follow the stratigraphy of the mound rather than dig mechanically along uniform horizontal lines.

- Moreover, as an ex-army brigadier, he brought with him a military precision to the practice of archaeology.

- The frontiers of the Harappan civilisation have little or no connection with present-day national boundaries. However, with the partition of the subcontinent and the creation of Pakistan, the major sites are now in Pakistani territory.

- This has spurred Indian archaeologists to try and locate sites in India. An extensive survey in Kutch has revealed a number of Harappan settlements and explorations in Punjab and Haryana have added to the list of Harappan sites.

- While Kalibangan, Lothal, Rakhi Garhi and most recently Dholavira have been discovered, explored and excavated as part of these efforts, fresh explorations continue.

- Over the decades, new issues have assumed importance. Where some archaeologists are often keen to obtain a cultural sequence, others try to understand the logic underlying the location of specific sites. They also grapple with the wealth of artefacts, trying to figure out the functions these may have served.

- Since the 1980s, there has also been growing international interest in Harappan archaeology. Specialists from the subcontinent and abroad have been jointly working at both Harappa and Mohenjodaro. They are using modern scientific techniques including surface exploration to recover traces of clay, stone, metal and plant and animal remains as well as to minutely analyse every scrap of available evidence. These explorations promise to yield interesting results in the future.

Problems of Piecing Together the Past

- As we have seen, it is not the Harappan script that helps in understanding the ancient civilisation. Rather, it is material evidence that allows archaeologists to better reconstruct Harappan life.

- This material could be pottery, tools, ornaments, household objects, etc. Organic materials such as cloth, leather, wood and reeds generally decompose, especially in tropical regions.

- What survive are stone, burnt clay (or terracotta), metal, etc. It is also important to remember that only broken or useless objects would have been thrown away. Other things would probably have been recycled.

- Consequently, valuable artefacts that are found intact were either lost in the past or hoarded and never retrieved. In other words, such finds are accidental rather than typical.

Classifying finds

- Recovering artefacts is just the beginning of the archaeological enterprise. Archaeologists then classify their finds.

- One simple principle of classification is in terms of material, such as stone, clay, metal, bone, ivory, etc.

- The second, and more complicated, is in terms of function: archaeologists have to decide whether, for instance, an artefact is a tool or an ornament, or both, or something meant for ritual use.

- An understanding of the function of an artefact is often shaped by its resemblance with present-day things – beads, querns, stone blades and pots are obvious examples.

- Archaeologists also try to identify the function of an artefact by investigating the context in which it was found: was it found in a house, in a drain, in a grave, in a kiln?

- Sometimes, archaeologists have to take recourse to indirect evidence. For instance, though there are traces of cotton at some Harappan sites, to find out about clothing we have to depend on indirect evidence including depictions in sculpture.

- Archaeologists have to develop frames of reference. We have seen that the first Harappan seal that was found could not be understood till archaeologists had a context in which to place it – both in terms of the cultural sequence in which it was found, and in terms of a comparison with finds in Mesopotamia.

Problems of interpretation

- The problems of archaeological interpretation are perhaps most evident in attempts to reconstruct religious practices.

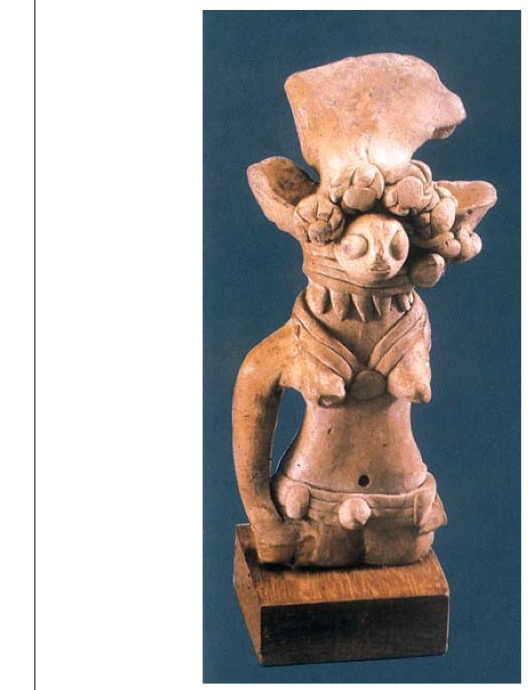

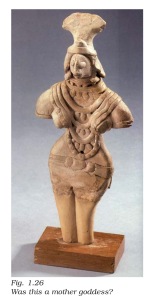

- Early archaeologists thought that certain objects which seemed unusual or unfamiliar may have had a religious significance. These included terracotta figurines of women, heavily jewelled, some with elaborate head-dresses. These were regarded as mother goddesses.

- Rare stone statuary of men in an almost standardised posture, seated with one hand on the knee – such as the “priest-king” – was also similarly classified. In other instances, structures have been assigned ritual significance. These include the Great Bath and fire altars found at Kalibangan and Lothal.

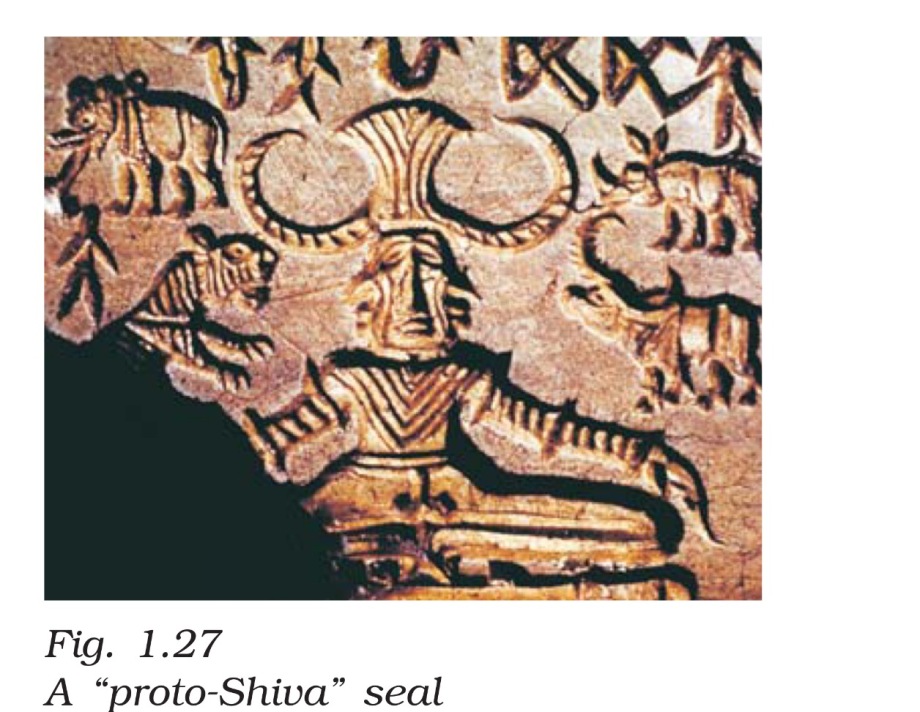

- Attempts have also been made to reconstruct religious beliefs and practices by examining seals, some of which seem to depict ritual scenes. Others, with plant motifs, are thought to indicate nature worship. Some animals – such as the one-horned animal, often called the “unicorn” – depicted on seals seem to be mythical, composite creatures.

- In some seals, a figure shown seated cross-legged in a “yogic” posture, sometimes surrounded by animals, has been regarded as a depiction of “proto-Shiva”, that is, an early form of one of the major deities of Hinduism.

- Besides, conical stone objects have been classified as lingas. Many reconstructions of Harappan religion are made on the assumption that later traditions provide parallels with earlier ones.

- This is because archaeologists often move from the known to the unknown, that is, from the present to the past. While this is plausible in the case of stone querns and pots, it becomes more speculative when we extend it to “religious” symbols.

- Let us look, for instance, at the “proto-Shiva” seals. The earliest religious text, the Rigveda (compiled c. 1500-1000 BCE) mentions a god named Rudra, which is a name used for Shiva in later Puranic traditions (in the first millennium CE;

- However, unlike Shiva, Rudra in the Rigveda is neither depicted as Pashupati (lord of animals in general and cattle in particular), nor as a yogi. In other words, this depiction does not match the description of Rudra in the Rigveda. Is this, then, possibly a shaman as some scholars have suggested?

- Shamans are men and women who claim magical and healing powers, as well as an ability to communicate with the other world.

What has been achieved after so many decades of archaeological work? We have a fairly good idea of the Harappan economy. We have been able to tease out social differences and we have some idea of how the civilisation functioned. It is really not clear how much more we would know if the script were to be deciphered. If a bilingual inscription is found, questions about the languages spoken by the Harappans could perhaps be put to rest. Several reconstructions remain speculative at present. Was the Great Bath a ritual structure? How widespread was literacy? Why do Harappan cemeteries show little social differentiation? Also unanswered are questions on gender – did women make pottery or did they only paint pots (as at present)? What about other craftspersons? What were the terracotta female figurines used for? Very few scholars have investigated issues of gender in the context of the Harappan civilisation and this is a whole new area for future work.