Topics

Languages and texts, major stages in the evolution of art and architecture, major philosophical thinkers and schools, ideas in Science and Mathematics.

Notes:

ARCHITECTURE

The iron pillar

- The iron pillar at Mehrauli, Delhi, is a remarkable example of the skill of Indian crafts persons.

- It is made of iron, 7.2. m high, and weighs over 3 tonnes.

- It was made about 1500 years ago. We know the date because there is an inscription on the pillar mentioning a ruler named Chandra, who probably belonged to the Gupta dynasty .

- What is amazing is the fact that the pillar has not rusted in all these years.

Buildings in brick and stone

- The skills of our crafts persons are also apparent in the buildings that have survived, such as stupas. The word stupa means a mound.

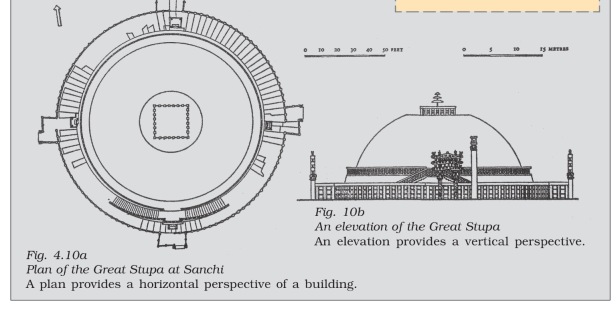

- The Great Stupa at Sanchi, Madhya Pradesh. Stupas like this one were built over several centuries. While the brick mound probably dates to the time of Ashoka, the railings and gateways were added during the time of later rulers.

- While there are several kinds of stupas, round and tall, big and small, these have certain common features.

- Generally, there is a small box placed at the centre or heart of the stupa. This may contain bodily remains (such as teeth, bone or ashes) of the Buddha or his followers, or things they used, as well as precious stones, and coins. This box, known as a relic casket, was covered with earth.

- Later, a layer of mud brick or baked brick was added on top. And then, the dome like structure was sometimes covered with carved stone slabs.

- Often, a path, known as the pradakshina patha, was laid around the stupa. This was surrounded with railings. Entrance to the path was through gateways.

- Devotees walked around the stupa, in a clockwise direction, as a mark of devotion.

- Both railings and gateways were often decorated with sculpture.

- Amaravati was a place where a magnificent stupa once existed. Many of the stone carvings for decorating the stupa were made about 2000 years ago. Other buildings were hollowed out of rock to make artificial caves. Some of these were very elaborately decorated with sculptures and painted walls.

- Some of the earliest Hindu temples were also built at this time. Deities such as Vishnu, Shiva, and Durga were worshipped in these shrines. The most important part of the temple was the room known as the garbhagriha, where the image of the chief deity was placed. It was here that priests performed religious rituals, and devotees offered worship to the deity.

- Often, as at Bhitargaon, a tower, known as the shikhara, was built on top of the garbhagriha, to mark this out as a sacred place. Building shikharas required careful planning.

- An early temple at Bhitargaon, Uttar Pradesh. This was built about 1500 years ago, and was made of baked brick and stone.

- Most temples also had a space known as the mandapa. It was a hall where people could assemble. At Mahabalipuram and Aihole some of the finest stone temples were built.

- Monolithic temples at Mahabalipuram : Each of these was carved out of a huge, single piece of stone (that is why they are known as monoliths). While brick structures are built up by adding layers of bricks from the bottom upwards, in this case the stone cutters had to work from top downwards.

- The Durga temple at Aihole, built about 1400 years ago:

How were stupas and temples built?

- There were several stages in building a stupa or a temple. Usually, kings or queens decided to build these as it was an expensive affair.

- First, good quality stone had to be found, quarried, and transported to the place that was often carefully chosen for the new building.

- Here, these rough blocks of stone had to be shaped and carved into pillars, and panels for walls, floors and ceilings.

- And then these had to be placed in precisely the right position.

- Kings and queens probably spent money from their treasury to pay the crafts persons who worked to build these splendid structures.

- Besides, when devotees came to visit the temple or the stupa, they often brought gifts, which were used to decorate the buildings.

- For example, an association of ivory workers paid for one of the beautiful gateways at Sanchi. Among the others who paid for decorations were merchants, farmers, garland makers, perfumers, smiths, and hundreds of men and women who are known only by their names which were inscribed on pillars, railings and walls.

- A Jaina monastery from Orissa. This two storey building was carved out of the rock surface. Jaina monks lived and meditated in these rooms.

Painting

- Ajanta is a place where several caves were hollowed out of the hills over centuries. Most of these were monasteries for Buddhist monks, and some of them were decorated with paintings.

- As the caves are dark inside, most of these paintings were done in the light of torches.

- The colours, which are vivid even after 1500 years, were made of plants and minerals.

- The artists who created these splendid works of art remain unknown.

The world of books

- Some of the best–known epics were written during this period. Epics are grand, long compositions, about heroic men and women, and include stories about gods.

- A famous Tamil epic, the Silappadikaram, was composed by a poet named Ilango, around 1800 years ago. It is the story of a merchant named Kovalan, who lived in Puhar and fell in love with a courtesan named Madhavi, neglecting his wife Kannagi. Later, he and Kannagi left Puhar and went to Madurai, where he was wrongly accused of theft by the court jeweller of the Pandya king. The king sentenced Kovalan to death. Kannagi, who still loved him, was full of grief and anger at this injustice, and destroyed the entire city of Madurai.

- A description from the Silappadikaram Here is how the poet describes Kannagi’s grief: “O witness of my grief, you cannot console me. Is it right that your body, fairer than pure gold, lies unwashed here in the dust? Is it just that in the red glow of the twilight, your handsome chest, framed with a flower wreath, lies thrown down on the bare earth, while I remain alone, helpless and abandoned to despair? Is there no god? Is there no god in this country? Can there be a god in a land where the sword of the king is used for the murder of innocent strangers? Is there no god, no god?”

- Another Tamil epic, the Manimekalai was composed by Sattanar around 1400 years ago. This describes the story of the daughter of Kovalan and Madhavi. These beautiful compositions were lost to scholars for many centuries, till their manuscripts were rediscovered, about a hundred years ago.

- Other writers, such as Kalidasa wrote in Sanskrit. A verse from the Meghaduta in which a monsoon cloud is imagined to be a messenger between lovers who are separated from one another. See how the poet describes the breeze that will carry the cloud northwards: “A cool breeze, delightful as it is touched With the fragrance of the earth Swollen by your showers, Inhaled deeply by elephants, And causing the wild figs to ripen, Will blow gently as you go.”

Recording and preserving old stories

- A number of Hindu religious stories that were in circulation earlier were written down around the same time. These include the Puranas. Purana literally mean old. The Puranas contain stories about gods and goddesses, such as Vishnu, Shiva, Durga or Parvati.

- They also contain details on how they were to be worshipped. Besides, there are accounts about the creation of the world, and about kings.

- The Puranas were written in simple Sanskrit verse, and were meant to be heard by everybody, including women and shudras, who were not allowed to study the Vedas. They were probably recited in temples by priests, and people came to listen to them.

- Two Sanskrit epics, the Mahabharata and Ramayana had been popular for a very long time.

- The Mahabharata is about a war fought between the Kauravas and Pandavas, who were cousins. This was a war to gain control of the throne of the Kurus, and their capital, Hastinapur. The story itself was an old one, but was written down in the form in which we know it today, about 1500 years ago.

- Both the Puranas and the Mahabharata are supposed to have been compiled by Vyasa. The Bhagavad Gita, was also included in the Mahabharata.

- The Ramayana is about Rama, a prince of Kosala, who was sent into exile. His wife Sita was abducted by the king of Lanka, named Ravana, and Rama had to fight a battle to get her back. He won and returned to Ayodhya, the capital of Kosala, after his victory. Like the Mahabharata, this was an old story that was now written down. Valmiki is recognised as the author of the Sanskrit Ramayana.

- There are several versions (many of which are performed) of the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, popular amongst people in different parts of the subcontinent.

- Ordinary people also told stories, composed poems and songs, sang, danced, and performed plays. Some of these are preserved in collections of stories such as the Jatakas and the Panchatantra, which were written down around this time. Stories from the Jatakas were often shown on the railings of stupas and in paintings in places such as Ajanta.

Writing books on science

- This was also the time when Aryabhata, a mathematician and astronomer, wrote a book in Sanskrit known as the Aryabhatiyam. He stated that day and night were caused by the rotation of the earth on its axis, even though it seems as if the sun is rising and setting everyday. He developed a scientific explanation for eclipses as well. He also found a way of calculating the circumference of a circle, which is nearly as accurate as the formula we use today. While numerals had been used earlier, mathematicians in India now invented a special symbol for zero.

- This system of counting was adapted by the Arabs and then spread to Europe. It continues to be in use throughout the world. The Romans used a system of counting without using zero.

What are the sources

- The sources that historians use to reconstruct this exciting world of ideas and beliefs include Buddhist, Jaina and Brahmanical texts, as well as a large and impressive body of material remains including monuments and inscriptions.

- Among the best preserved monuments of the time is the stupa at Sanchi.

A Glimpse of Sanchi

- The most wonderful ancient buildings in the state of Bhopal are at Sanchi Kanakhera. The ruins appear to be the object of great interest to European gentlemen.

- Major Alexander Cunningham stayed several weeks in this neighbourhood and examined these ruins most carefully. He took drawings of the place, deciphered the inscription, and bored shafts down these domes. The results of his investigations were described by him in an English work.

- Nineteenth-century Europeans were very interested in the stupa at Sanchi. In fact, the French sought Shahjehan Begum’s permission to take away the eastern gateway, which was the best preserved, to be displayed in a museum in France.

- For a while some Englishmen also wanted to do the same, but fortunately both the French and the English were satisfied with carefully prepared plaster-cast copies and the original remained at the site, part of the Bhopal state.

- The rulers of Bhopal, Shahjehan Begum and her successor Sultan Jehan Begum, provided money for the preservation of the ancient site. No wonder then that John Marshall dedicated his important volumes on Sanchi to Sultan Jehan.

- She funded the museum that was built there as well as the guesthouse where he lived and wrote the volumes. She also funded the publication of the volumes.

- So if the stupa complex has survived, it is in no small measure due to wise decisions, and to good luck in escaping the eyes of railway contractors, builders, and those looking for finds to carry away to the museums of Europe.

- One of the most important Buddhist centres, the discovery of Sanchi has vastly transformed our understanding of early Buddhism. Today it stands testimony to the successful restoration and preservation of a key archaeological site by the Archaeological Survey of India.

The Background: Sacrifices and Debates

- The mid-first millennium BCE is often regarded as a turning point in world history: it saw the emergence of thinkers such as Zarathustra in Iran, Kong Zi in China, Socrates, Plato and Aristotle in Greece, and Mahavira and Gautama Buddha, among many others, in India.

- They tried to understand the mysteries of existence and the relationship between human beings and the cosmic order.

- This was also the time when new kingdoms and cities were developing and social and economic life was changing in a variety of ways in the Ganga valley. These thinkers attempted to understand these developments as well.

The sacrificial tradition

- There were several pre-existing traditions of thought, religious belief and practice, including the early Vedic tradition, known from the Rigveda, compiled between c.1500 and 1000 BCE.

- The Rigveda consists of hymns in praise of a variety of deities, especially Agni, Indra and Soma. Many of these hymns were chanted when sacrifices were performed, where people prayed for cattle, sons, good health, long life, etc.

- At first, sacrifices were performed collectively. Later (c. 1000 BCE-500 BCE onwards) some were performed by the heads of households for the well- being of the domestic unit.

- More elaborate sacrifices, such as the rajasuya and ashvamedha, were performed by chiefs and kings who depended on Brahmana priests to conduct the ritual.

New questions

- Many ideas found in the Upanishads (c. sixth century BCE onwards) show that people were curious about the meaning of life, the possibility of life after death, and rebirth.

- Was rebirth due to past actions? Such issues were hotly debated. Thinkers were concerned with understanding and expressing the nature of the ultimate reality. And others, outside the Vedic tradition, asked whether or not there even was a single ultimate reality.

- People also began speculating on the significance of the sacrificial tradition.

Debates and discussions

- We get a glimpse of lively discussions and debates from Buddhist texts, which mention as many as 64 sects or schools of thought.

- Teachers travelled from place to place, trying to convince one another as well as laypersons, about the validity of their philosophy or the way they understood the world.

- Debates took place in the kutagarashala – literally, a hut with a pointed roof – or in groves where travelling mendicants halted.

- If a philosopher succeeded in convincing one of his rivals, the followers of the latter also became his disciples. So support for any particular sect could grow and shrink over time.

- Many of these teachers, including Mahavira and the Buddha, questioned the authority of the Vedas. They also emphasised individual agency – suggesting that men and women could strive to attain liberation from the trials and tribulations of worldly existence.

- This was in marked contrast to the Brahmanical position, wherein, an individual’s existence was thought to be determined by his or her birth in a specific caste or gender.

How Buddhist texts were prepared and preserved

- The Buddha (and other teachers) taught orally – through discussion and debate. Men and women (perhaps children as well) attended these discourses and discussed what they heard.

- None of the Buddha’s speeches were written down during his lifetime. After his death (c. fifth-fourth century BCE) his teachings were compiled by his disciples at a council of “elders” or senior monks at Vesali (Pali for Vaishali in present-day Bihar). These compilations were known as Tipitaka – literally, three baskets to hold different types of texts.

- They were first transmitted orally and then written and classified according to length as well as subject matter.

- The Vinaya Pitaka included rules and regulations for those who joined the sangha or monastic order; the Buddha’s teachings were included in the Sutta Pitaka; and the Abhidhamma Pitaka dealt with philosophical matters.

- Each pitaka comprised a number of individual texts. Later, commentaries were written on these texts by Buddhist scholars.

- As Buddhism travelled to new regions such as Sri Lanka, other texts such as the Dipavamsa (literally, the chronicle of the island) and Mahavamsa (the great chronicle) were written, containing regional histories of Buddhism.

- Many of these works contained biographies of the Buddha. Some of the oldest texts are in Pali, while later compositions are in Sanskrit.

- When Buddhism spread to East Asia, pilgrims such as Fa Xian and Xuan Zang travelled all the way from China to India in search of texts. These they took back to their own country, where they were translated by scholars.

- Indian Buddhist teachers also travelled to faraway places, carrying texts to disseminate the teachings of the Buddha. Buddhist texts were preserved in manuscripts for several centuries in monasteries in different parts of Asia.

- Modern translations have been prepared from Pali, Sanskrit, Chinese and Tibetan texts.

The Message of Mahavira

- The basic philosophy of the Jainas was already in existence in north India before the birth of Vardhamana, who came to be known as Mahavira, in the sixth century BCE.

- According to Jaina tradition, Mahavira was preceded by 23 other teachers or tirthankaras – literally, those who guide men and women across the river of existence.

- The most important idea in Jainism is that the entire world is animated: even stones, rocks and water have life.

- Non-injury to living beings, especially to humans, animals, plants and insects, is central to Jaina philosophy. In fact the principle of ahimsa, emphasised within Jainism, has left its mark on Indian thinking as a whole.

- According to Jaina teachings, the cycle of birth and rebirth is shaped through karma. Asceticism and penance are required to free oneself from the cycle of karma. This can be achieved only by renouncing the world; therefore, monastic existence is a necessary condition of salvation.

- Jaina monks and nuns took five vows: to abstain from killing, stealing and lying; to observe celibacy; and to abstain from possessing property.

The spread of Jainism

- Gradually, Jainism spread to many parts of India. Like the Buddhists, Jaina scholars produced a wealth of literature in a variety of languages – Prakrit, Sanskrit and Tamil.

- For centuries, manuscripts of these texts were carefully preserved in libraries attached to temples.

- Some of the earliest stone sculptures associated with religious traditions were produced by devotees of the Jaina tirthankaras, and have been recovered from several sites throughout the subcontinent.

The Buddha and the Quest for Enlightenment

- One of the most influential teachers of the time was the Buddha. Over the centuries, his message spread across the subcontinent and beyond – through Central Asia to China, Korea and Japan, and through Sri Lanka, across the seas to Myanmar, Thailand and Indonesia.

- How do we know about the Buddha’s teachings? These have been reconstructed by carefully editing, translating and analysing the Buddhist texts mentioned earlier.

- Historians have also tried to reconstruct details of his life from hagiographies ( Hagiography is a biography of a saint or religious leader. Hagiographies often praise the saint’s achievements, and may not always be literally accurate. They are important because they tell us about the beliefs of the followers of that particular tradition. ).

- Many of these were written down at least a century after the time of the Buddha, in an attempt to preserve memories of the great teacher.

- According to these traditions, Siddhartha, as the Buddha was named at birth, was the son of a chief of the Sakya clan. He had a sheltered upbringing within the palace, insulated from the harsh realities of life.

- One day he persuaded his charioteer to take him into the city. His first journey into the world outside was traumatic. He was deeply anguished when he saw an old man, a sick man and a corpse.

- He realised in that moment that the decay and destruction of the human body was inevitable. He also saw a homeless mendicant, who, it seemed to him, had come to terms with old age, disease and death, and found peace.

- Siddhartha decided that he too would adopt the same path. Soon after, he left the palace and set out in search of his own truth. Siddhartha explored several paths including bodily mortification which led him to a situation of near death.

- Abandoning these extreme methods, he meditated for several days and finally attained enlightenment. After this he came to be known as the Buddha or the Enlightened One.

- For the rest of his life, he taught dhamma or the path of righteous living.

The Teachings of the Buddha

- The Buddha’s teachings have been reconstructed from stories, found mainly in the Sutta Pitaka. Although some stories describe his miraculous powers, others suggest that the Buddha tried to convince people through reason and persuasion rather than through displays of supernatural power.

- For instance, when a grief-stricken woman whose child had died came to the Buddha, he gently convinced her about the inevitability of death rather than bring her son back to life.

- These stories were narrated in the language spoken by ordinary people so that these could be easily understood.

- According to Buddhist philosophy, the world is transient (anicca) and constantly changing; it is also soulless (anatta) as there is nothing permanent or eternal in it. Within this transient world, sorrow (dukkha) is intrinsic to human existence. It is by following the path of moderation between severe penance and self-indulgence that human beings can rise above these worldly troubles.

- In the earliest forms of Buddhism, whether or not god existed was irrelevant. The Buddha regarded the social world as the creation of humans rather than of divine origin. Therefore, he advised kings and gahapatis to be humane and ethical.

- Individual effort was expected to transform social relations. The Buddha emphasised individual agency and righteous action as the means to escape from the cycle of rebirth and attain self-realisation and nibbana, literally the extinguishing of the ego and desire – and thus end the cycle of suffering for those who renounced the world.

- According to Buddhist tradition, his last words to his followers were: “Be lamps unto yourselves as all of you must work out your own liberation.”

Followers of the Buddha

- Soon there grew a body of disciples of the Buddha and he founded a sangha, an organisation of monks who too became teachers of dhamma.

- These monks lived simply, possessing only the essential requisites for survival, such as a bowl to receive food once a day from the laity. As they lived on alms, they were known as bhikkhus.

- Initially, only men were allowed into the sangha, but later women also came to be admitted.

- According to Buddhist texts, this was made possible through the mediation of Ananda, one of the Buddha’s dearest disciples, who persuaded him to allow women into the sangha.

- The Buddha’s foster mother, Mahapajapati Gotami was the first woman to be ordained as a bhikkhuni.

- Many women who entered the sangha became teachers of dhamma and went on to become theris, or respected women who had attained liberation.

- The Buddha’s followers came from many social groups. They included kings, wealthy men and gahapatis, and also humbler folk: workers, slaves and craftspeople.

- Once within the sangha, all were regarded as equal, having shed their earlier social identities on becoming bhikkhus and bhikkhunis.

- The internal functioning of the sangha was based on the traditions of ganas and sanghas, where consensus was arrived at through discussions. If that failed, decisions were taken by a vote on the subject.

- Buddhism grew rapidly both during the lifetime of the Buddha and after his death, as it appealed to many people dissatisfied with existing religious practices and confused by the rapid social changes taking place around them.

- The importance attached to conduct and values rather than claims of superiority based on birth, the emphasis placed on metta (fellow feeling) and karuna (compassion), especially for those who were younger and weaker than oneself, were ideas that drew men and women to Buddhist teachings.

Stupas

- We have seen that Buddhist ideas and practices emerged out of a process of dialogue with other traditions – including those of the Brahmanas, Jainas and several others, not all of whose ideas and practices were preserved in texts. Some of these interactions can be seen in the ways in which sacred places came to be identified.

- From earliest times, people tended to regard certain places as sacred. These included sites with special trees or unique rocks, or sites of awe- inspiring natural beauty. These sites, with small shrines attached to them, were sometimes described as chaityas.

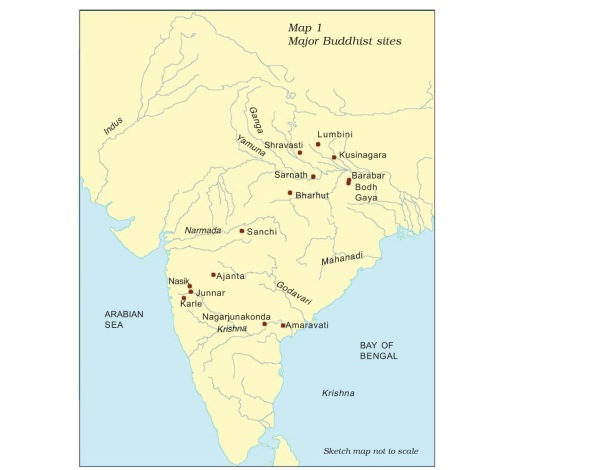

- Buddhist literature mentions several chaityas. It also describes places associated with the Buddha’s life – where he was born (Lumbini), where he attained enlightenment (Bodh Gaya), where he gave his first sermon (Sarnath) and where he attained nibbana (Kusinagara).

- Gradually, each of these places came to be regarded as sacred.

- About 200 years after the time of the Buddha, Asoka erected a pillar at Lumbini to mark the fact that he had visited the place.

Why were stupas built

- There were other places too that were regarded as sacred. This was because relics of the Buddha such as his bodily remains or objects used by him were buried there. These were mounds known as stupas.

- The tradition of erecting stupas may have been pre-Buddhist, but they came to be associated with Buddhism.

- Since they contained relics regarded as sacred, the entire stupa came to be venerated as an emblem of both the Buddha and Buddhism.

- According to a Buddhist text known as the Ashokavadana, Asoka distributed portions of the Buddha’s relics to every important town and ordered the construction of stupas over them.

- By the second century BCE a number of stupas, including those at Bharhut, Sanchi and Sarnath, had been built.

How were stupas built

- Inscriptions found on the railings and pillars of stupas record donations made for building and decorating them. Some donations were made by kings such as the Satavahanas; others were made by guilds, such as that of the ivory workers who financed part of one of the gateways at Sanchi.

- Hundreds of donations were made by women and men who mention their names, sometimes adding the name of the place from where they came, as well as their occupations and names of their relatives.

- Bhikkhus and bhikkhunis also contributed towards building these monuments.

The structure of the stupa

- The stupa (a Sanskrit word meaning a heap) originated as a simple semi-circular mound of earth, later called anda.

- Gradually, it evolved into a more complex structure, balancing round and square shapes. Above the anda was the harmika, a balcony- like structure that represented the abode of the gods.

- Arising from the harmika was a mast called the yashti, often surmounted by a chhatri or umbrella.

- Around the mound was a railing, separating the sacred space from the secular world.

- The early stupas at Sanchi and Bharhut were plain except for the stone railings, which resembled a bamboo or wooden fence, and the gateways, which were richly carved and installed at the four cardinal points.

- Worshippers entered through the eastern gateway and walked around the mound in a clockwise direction keeping the mound on the right, imitating the sun’s course through the sky.

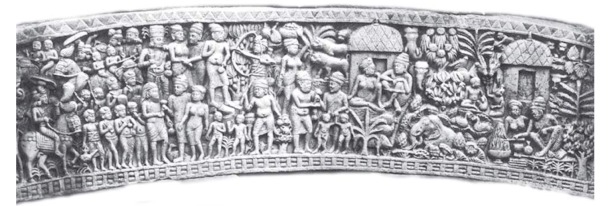

- Later, the mound of the stupas came to be elaborately carved with niches and sculptures as at Amaravati, and Shah- ji-ki-Dheri in Peshawar (Pakistan).

Discovering” Stupas

The Fate of Amaravati and Sanchi

- In 1796, a local raja who wanted to build a temple stumbled upon the ruins of the stupa at Amaravati. He decided to use the stone, and thought there might be some treasure buried in what seemed to be a hill.

- Some years later, a British official named Colin Mackenzie visited the site. Although he found several pieces of sculpture and made detailed drawings of them, these reports were never published.

- In 1854, Walter Elliot, the commissioner of Guntur (Andhra Pradesh), visited Amaravati and collected several sculpture panels and took them away to Madras. (These came to be called the Elliot marbles after him.)

- He also discovered the remains of the western gateway and came to the conclusion that the structure at Amaravati was one of the largest and most magnificent Buddhist stupas ever built.

- By the 1850s, some of the slabs from Amaravati had begun to be taken to different places: to the Asiatic Society of Bengal at Calcutta, to the India Office in Madras and some even to London.

- It was not unusual to find these sculptures adorning the gardens of British administrators. In fact, any new official in the area continued to remove sculptures from the site on the grounds that earlier officials had done the same.

- One of the few men who had a different point of view was an archaeologist named H.H. Cole. He wrote: “It seems to me a suicidal and indefensible policy to allow the country to be looted of original works of ancient art.”

- He believed that museums should have plaster-cast facsimiles of sculpture, whereas the originals should remain where they had been found. Unfortunately, Cole did not succeed in convincing the authorities about Amaravati, although his plea for in situ preservation was adopted in the case of Sanchi.

Why did Sanchi survive while Amaravati did not?

- Perhaps Amaravati was discovered before scholars understood the value of the finds and realised how critical it was to preserve things where they had been found instead of removing them from the site.

- When Sanchi was “discovered” in 1818, three of its four gateways were still standing, the fourth was lying on the spot where it had fallen and the mound was in good condition.

- Even so, it was suggested that the gateway be taken to either Paris or London; finally a number of factors helped to keep Sanchi as it was, and so it stands, whereas the mahachaitya at Amaravati is now just an insignificant little mound, totally denuded of its former glory.

Sculpture

- We have just seen how sculptures were removed from stupas and transported all the way to Europe. This happened partly because those who saw them considered them to be beautiful and valuable, and wanted to keep them for themselves.

Stories in stone

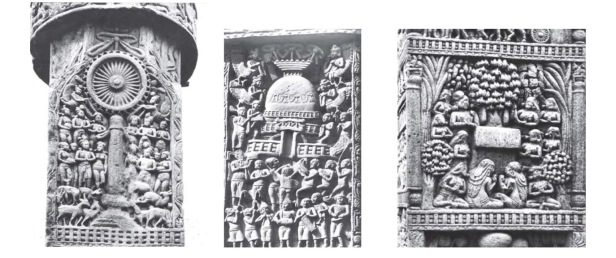

- At first sight the sculpture seems to depict a rural scene, with thatched huts and trees. However, art historians who have carefully studied the sculpture at Sanchi identify it as a scene from the Vessantara Jataka.

- This is a story about a generous prince who gave away everything to a Brahmana, and went to live in the forest with his wife and children.

- As you can see in this case, historians often try to understand the meaning of sculpture by comparing it with textual evidence.

Symbols of worship

- Art historians had to acquire familiarity with hagiographies of the Buddha in order to understand Buddhist sculpture.

- According to hagiographies, the Buddha attained enlightenment while meditating under a tree. Many early sculptors did not show the Buddha in human form – instead, they showed his presence through symbols.

- Fig (far right) Worshipping the Bodhi tree Notice the tree, the seat, and the people around it. Fig (middle right) Worshipping the stupa Fig. (below) Setting in motion the wheel of dharma

- The empty seat was meant to indicate the meditation of the Buddha, and the stupa was meant to represent the mahaparinibbana.

- Another frequently used symbol was the wheel. This stood for the first sermon of the Buddha, delivered at Sarnath.

- As is obvious, such sculptures cannot be understood literally – for instance, the tree does not stand simply for a tree, but symbolises an event in the life of the Buddha.

- In order to understand such symbols, historians have to familiarise themselves with the traditions of those who produced these works of art.

Popular traditions

- Other sculptures at Sanchi were perhaps not directly inspired by Buddhist ideas. These include beautiful women swinging from the edge of the gateway, holding onto a tree. Initially, scholars were a bit intrigued about this image, which seemed to have little to do with renunciation.

- However, after examining other literary traditions, they realised that it could be a representation of what is described in Sanskrit as a shalabhanjika.

- According to popular belief, this was a woman whose touch caused trees to flower and bear fruit. It is likely that this was regarded as an auspicious symbol and integrated into the decoration of the stupa.

- The shalabhanjika motif suggests that many people who turned to Buddhism enriched it with their own pre-Buddhist and even non-Buddhist beliefs, practices and ideas.

- Some of the recurrent motifs in the sculpture at Sanchi were evidently derived from these traditions.

- There are other images as well. For instance, some of the finest depictions of animals are found there. These animals include elephants, horses, monkeys and cattle.

- While the Jatakas contain several animal stories that are depicted at Sanchi, it is likely that many of these animals were carved to create lively scenes to draw viewers.

- Also, animals were often used as symbols of human attributes. Elephants, for example, were depicted to signify strength and wisdom.

- Another motif is that of a woman surrounded by lotuses and elephants, which seem to be sprinkling water on her as if performing an abhisheka or consecration. While some historians identify the figure as Maya, the mother of the Buddha, others identify her with a popular goddess, Gajalakshmi – literally, the goddess of good fortune – who is associated with elephants.

- It is also possible that devotees who saw these sculptures identified the figure with both Maya and Gajalakshmi.

- Consider, too, the serpent, which is found on several pillars. This motif seems to be derived from popular traditions, which were not always recorded in texts.

- Interestingly, one of the earliest modern art historians, James Fergusson, considered Sanchi to be a centre of tree and serpent worship. He was not familiar with Buddhist literature – most of which had not yet been translated – and arrived at this conclusion by studying only the images on their own.

New Religious Traditions

The development of Mahayana Buddhism

- By the first century CE, there is evidence of changes in Buddhist ideas and practices. Early Buddhist teachings had given great importance to self-effort in achieving nibbana. Besides, the Buddha was regarded as a human being who attained enlightenment and nibbana through his own efforts.

- However, gradually the idea of a saviour emerged. It was believed that he was the one who could ensure salvation. Simultaneously, the concept of the Bodhisatta also developed. Bodhisattas were perceived as deeply compassionate beings who accumulated merit through their efforts but used this not to attain nibbana and thereby abandon the world, but to help others.

- The worship of images of the Buddha and Bodhisattas became an important part of this tradition. This new way of thinking was called Mahayana – literally, the “great vehicle”. Those who adopted these beliefs described the older tradition as Hinayana or the “lesser vehicle”.

The growth of Puranic Hinduism

- The notion of a saviour was not unique to Buddhism. We find similar ideas being developed in different ways within traditions that we now consider part of Hinduism. These included Vaishnavism (a form of Hinduism within which Vishnu was worshipped as the principal deity) and Shaivism (a tradition within which Shiva was regarded as the chief god), in which there was growing emphasis on the worship of a chosen deity.

- In such worship the bond between the devotee and the god was visualised as one of love and devotion, or bhakti.

- In the case of Vaishnavism, cults developed around the various avatars or incarnations of the deity. Ten avatars were recognised within the tradition. These were forms that the deity was believed to have assumed in order to save the world whenever it was threatened by disorder and destruction because of the dominance of evil forces.

- It is likely that different avatars were popular in different parts of the country. Recognising each of these local deities as a form of Vishnu was one way of creating a more unified religious tradition.

- Some of these forms were represented in sculptures, as were other deities. Shiva, for instance, was symbolised by the linga, although he was occasionally represented in human form too.

- All such representations depicted a complex set of ideas about the deities and their attributes through symbols such as head- dresses, ornaments and ayudhas – weapons or auspicious objects the deities hold in their hands – how they are seated, etc.

- To understand the meanings of these sculptures historians have to be familiar with the stories behind them – many of which are contained in the Puranas, compiled by Brahmanas (by about the middle of the first millennium CE).

- They contained much that had been composed and been in circulation for centuries, including stories about gods and goddesses. Generally, they were written in simple Sanskrit verse, and were meant to be read aloud to everybody, including women and Shudras, who did not have access to Vedic learning.

- Much of what is contained in the Puranas evolved through interaction amongst people – priests, merchants, and ordinary men and women who travelled from place to place sharing ideas and beliefs.

- We know for instance that Vasudeva-Krishna was an important deity in the Mathura region. Over centuries, his worship spread to other parts of the country as well.

Building temples

- Around the time that the stupas at sites such as Sanchi were acquiring their present form, the first temples to house images of gods and goddesses were also being built.

- The early temple was a small square room, called the garbhagriha, with a single doorway for the worshipper to enter and offer worship to the image.

- Gradually, a tall structure, known as the shikhara, was built over the central shrine. Temple walls were often decorated with sculpture.

- Later temples became far more elaborate – with assembly halls, huge walls and gateways, and arrangements for supplying water.

- One of the unique features of early temples was that some of these were hollowed out of huge rocks, as artificial caves.

- The tradition of building artificial caves was an old one. Some of the earliest of these were constructed in the third century BCE on the orders of Asoka for renouncers who belonged to the Ajivika sect.

- This tradition evolved through various stages and culminated much later – in the eighth century – in the carving out of an entire temple, that of Kailashnatha (a name of Shiva).

- A copperplate inscription records the amazement of the chief sculptor after he completed the temple at Ellora: “Oh how did I make it!”

Can We “See” Everything?

Grappling with the unfamiliar

- It will be useful to recall that when nineteenth- century European scholars first saw some of the sculptures of gods and goddesses, they could not understand what these were about.

- Sometimes, they were horrified by what seemed to them grotesque figures, with multiple arms and heads or with combinations of human and animal forms.

- These early scholars tried to make sense of what appeared to be strange images by comparing them with sculpture with which they were familiar, that from ancient Greece. While they often found early Indian sculpture inferior to the works of Greek artists, they were very excited when they discovered images of the Buddha and Bodhisattas that were evidently based on Greek models.

- These were, more often than not, found in the northwest, in cities such as Taxila and Peshawar, where Indo-Greek rulers had established kingdoms in the second century BCE.

- As these images were closest to the Greek statues these scholars were familiar with, they were considered to be the best examples of early Indian art. In effect, these scholars adopted a strategy we all frequently use – devising yardsticks derived from the familiar to make sense of the unfamiliar.

If text and image do not match …

- Consider another problem. We have seen that art historians often draw upon textual traditions to understand the meaning of sculptures.

- While this is certainly a far more efficacious strategy than comparing Indian images with Greek statues, it is not always easy to use.

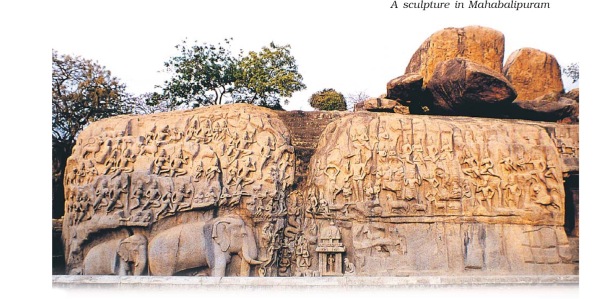

- One of the most intriguing examples of this is a famous sculpture along a huge rock surface in Mahabalipuram (Tamil Nadu).

- Clearly, Fig. is a vivid depiction of a story. But which story is it?

- Art historians have searched through the Puranas to identify it and are sharply divided in their opinions.

- Some feel that this depicts the descent of the river Ganga from heaven – the natural cleft through the centre of the rock surface might represent the river. The story itself is narrated in the Puranas and the epics.

- Others feel that it represents a story from the Mahabharata – Arjuna doing penance on the river bank in order to acquire arms – pointing to the central figure of an ascetic.