Topic covers

Formation of States (Mahajanapada) :Republics and monarchies; Rise of urbancentres; Trade routes; Economic growth;Introduction of coinage; Spread of Jainism and Buddhism; Rise of Magadhaand Nandas.Iranian and Macedonian invasions and their impact.

Theory

There were several developments in different parts of the subcontinent during the long span of 1,500 years following the end of the Harappan civilisation. This was also the period during which the Rigveda was composed by people living along the Indus and its tributaries. Agricultural settlements emerged in many parts of the subcontinent, including north India, the Deccan Plateau, and parts of Karnataka. Besides, there is evidence of pastoral populations in the Deccan and further south. New modes of disposal of the dead, including the making of elaborate stone structures known as megaliths, emerged in central and south India from the first millennium BCE. In many cases, the dead were buried with a rich range of iron tools and weapons. From c. sixth century BCE, there is evidence that there were other trends as well. Perhaps the most visible was the emergence of early states, empires and kingdoms. Underlying these political processes were other changes, evident in the ways in which agricultural production was organised. Simultaneously, new towns appeared almost throughout the subcontinent. Historians attempt to understand these developments by drawing on a range of sources – inscriptions, texts, coins and visual material.

How some men became rulers

- Choosing leaders or rulers by voting is something that has become common during the last fifty years or so. How did men become rulers in the past?

- Some of the rajas were probably chosen by the jana, the people. But, around 3000 years ago, we find some changes taking place in the ways in which rajas were chosen.

- Some men now became recognised as rajas by performing very big sacrifices. The ashvamedha or horse sacrifice was one such ritual.

- A horse was let loose to wander freely and it was guarded by the raja’s men. If the horse wandered into the kingdoms of other rajas and they stopped it, they had to fight. If they allowed the horse to pass, it meant that they accepted that the raja who wanted to perform the sacrifice was stronger than them.

- These rajas were then invited to the sacrifice, which was performed by specially trained priests, who were rewarded with gifts.

- The raja who organised the sacrifice was recognised as being very powerful, and all those who came brought gifts for him. The raja was a central figure in these rituals. He often had a special seat, a throne or a tiger skin. His charioteer, who was his companion in the battle field and witnessed his exploits, chanted tales of his glory.

- His relatives, especially his wives and sons, had to perform a variety of minor rituals. The other rajas were simply spectators who had to sit and watch the performance of the sacrifice.

- Priests performed the rituals including the sprinkling of sacred water on the king. The ordinary people, the vish or vaishya, also brought gifts.

- However, some people, such as those who were regarded as shudras by the priests, were excluded from many rituals.

Varnas

- We have many books that were composed in north India, especially in the areas drained by the Ganga and the Yamuna, during this period.

- These books are often called later Vedic, because they were composed after the Rigveda.

- These include the Samaveda, Yajurveda and Atharvaveda, as well as other books.

- These were composed by priests, and described how rituals were to be performed. They also contained rules about society.

- There were several different groups in society at this time — priests and warriors, farmers, herders, traders, crafts persons, labourers, fishing folk, and forest people.

- Some priests and warriors were rich, as were some farmers and traders. Others, including many herders, crafts persons, labourers, fishing folk and hunters and gatherers, were poor.

- The priests divided people into four groups, called varnas.

- According to them, each varna had a different set of functions. The first varna was that of the brahmin.

- Brahmins were expected to study (and teach) the Vedas, perform sacrifices and receive gifts.

- In the second place were the rulers, also known as kshatriyas. They were expected to fight battles and protect people.

- Third were the vish or the vaishyas. They were expected to be farmers, herders, and traders. Both the kshatriyas and the vaishyas could perform sacrifices.

- Last were the shudras, who had to serve the other three groups and could not perform any rituals. Often, women were also grouped with the shudras.

- Both women and shudras were not allowed to study the Vedas.

- The priests also said that these groups were decided on the basis of birth. For example, if one’s father and mother were brahmins one would automatically become a brahmin, and so on.

- Later, they classified some people as untouchable. These included some crafts persons, hunters and gatherers, as well as people who helped perform burials and cremations.

- The priests said that contact with these groups was polluting.

- Many people did not accept the system of varna laid down by the brahmins. Some kings thought they were superior to the priests. Others felt that birth could not be a basis for deciding which varna people belonged to.

- Besides, some people felt that there should be no differences amongst people based on occupation. Others felt that everybody should be able to perform rituals. And others condemned the practice of untouchability.

- Also, there were many areas in the subcontinent, such as the north-east, where social and economic differences were not very sharp, and where the influence of the priests was limited.

Prinsep and Piyadassi

- Some of the most momentous developments in Indian epigraphy took place in the 1830s.

- This was when James Prinsep, an officer in the mint of the East India Company, deciphered Brahmi and Kharosthi, two scripts used in the earliest inscriptions and coins.

- He found that most of these mentioned a king referred to as Piyadassi – meaning “pleasant to behold”; there were a few inscriptions which also referred to the king as Asoka, one of the most famous rulers known from Buddhist texts.

- This gave a new direction to investigations into early Indian political history as European and Indian scholars used inscriptions and texts composed in a variety of languages to reconstruct the lineages of major dynasties that had ruled the subcontinent.

- As a result, the broad contours of political history were in place by the early decades of the twentieth century. Subsequently, scholars began to shift their focus to the context of political history, investigating whether there were connections between political changes and economic and social developments. It was soon realised that while there were links, these were not always simple or direct.

Janapadas

- The rajas who performed these big sacrifices were now recognised as being rajas of janapadas rather than janas.

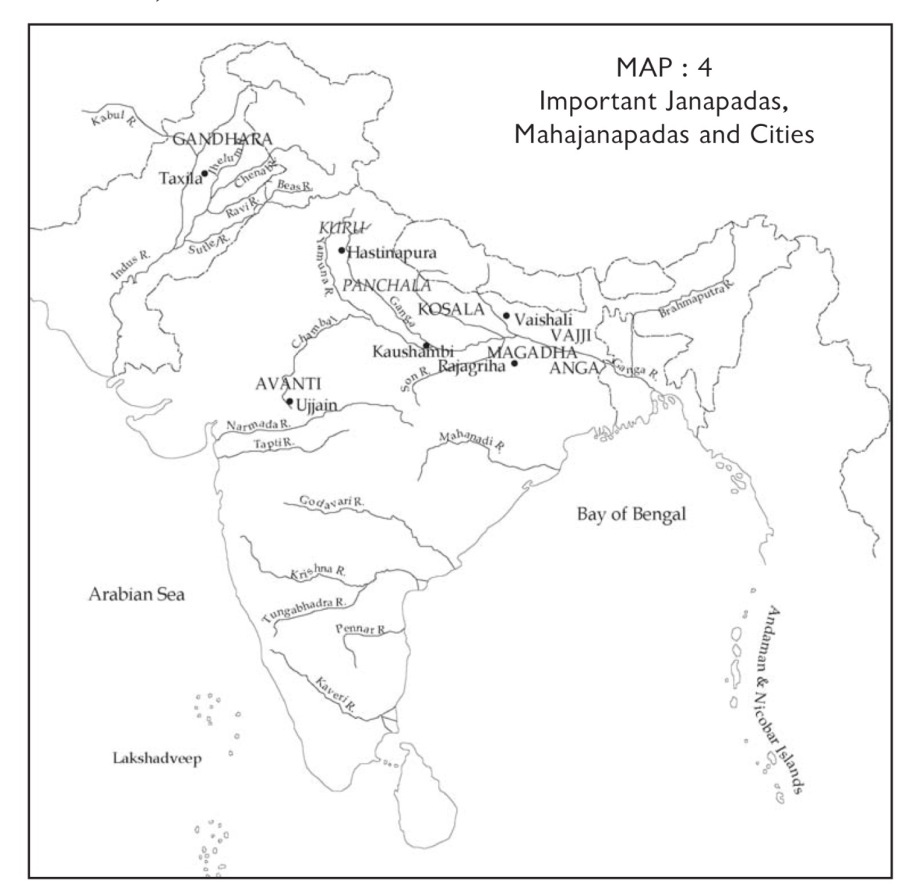

- The word janapada literally means the land where the jana set its foot, and settled down. Some important janapadas are shown on Map.

- Archaeologists have excavated a number of settlements in these janapadas, such as Purana Qila in Delhi, Hastinapur near Meerut, and Atranjikhera, near Etah (the last two are in Uttar Pradesh).

- They found that people lived in huts, and kept cattle as well as other animals.

- They also grew a variety of crops — rice, wheat, barley, pulses, sugarcane, sesame and mustard.

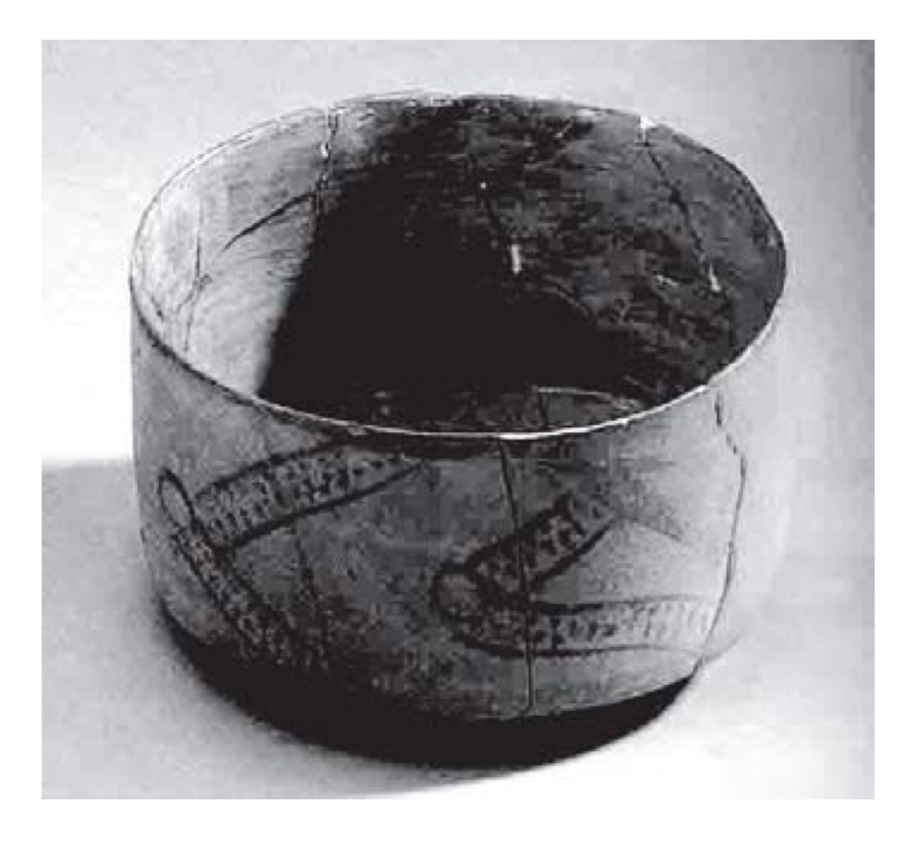

- They made earthen pots. Some of these were grey in colour, others were red.

- One special type of pottery found at these sites is known as Painted Grey Ware.

- As is obvious from the name, these grey pots had painted designs, usually simple lines and geometric patterns.

- Plates and bowls are the most common vessels made out of Painted Grey Ware. These are extremely fine to touch, with a nice, smooth surface.

- Perhaps these were used on special occasions, for important people, and to serve special food.

Mahajanapadas

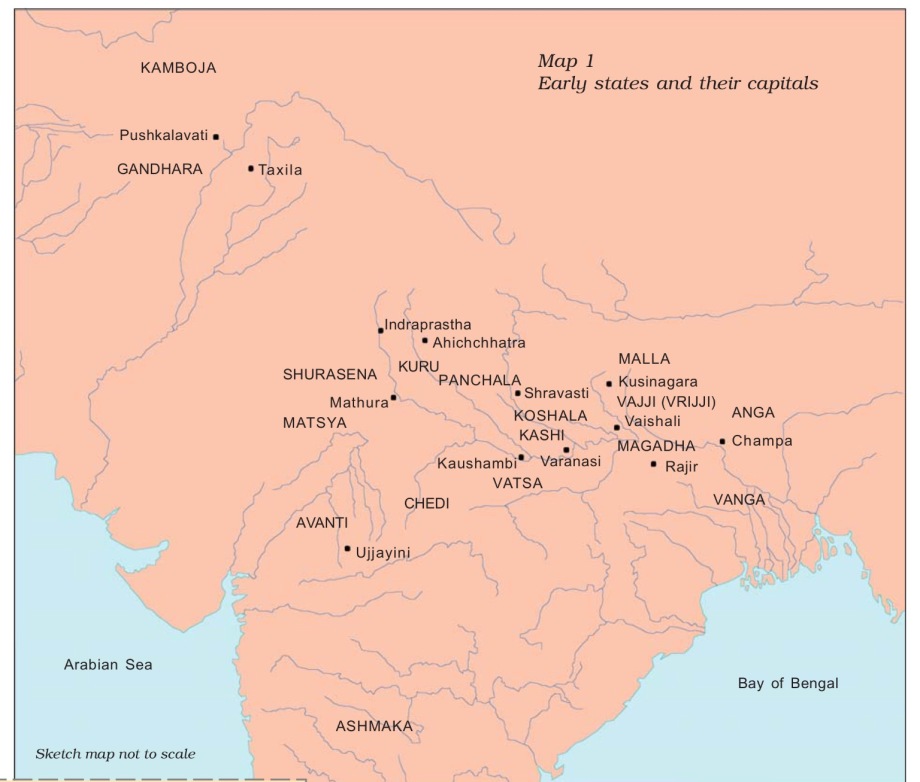

- About 2500 years ago, some janapadas became more important than others, and were known as mahajanapadas.

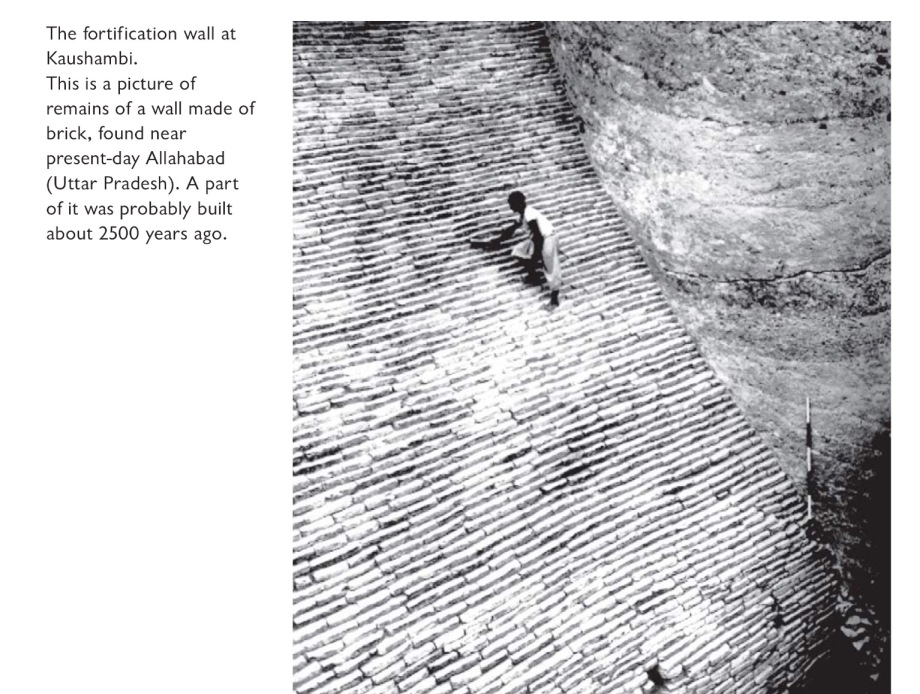

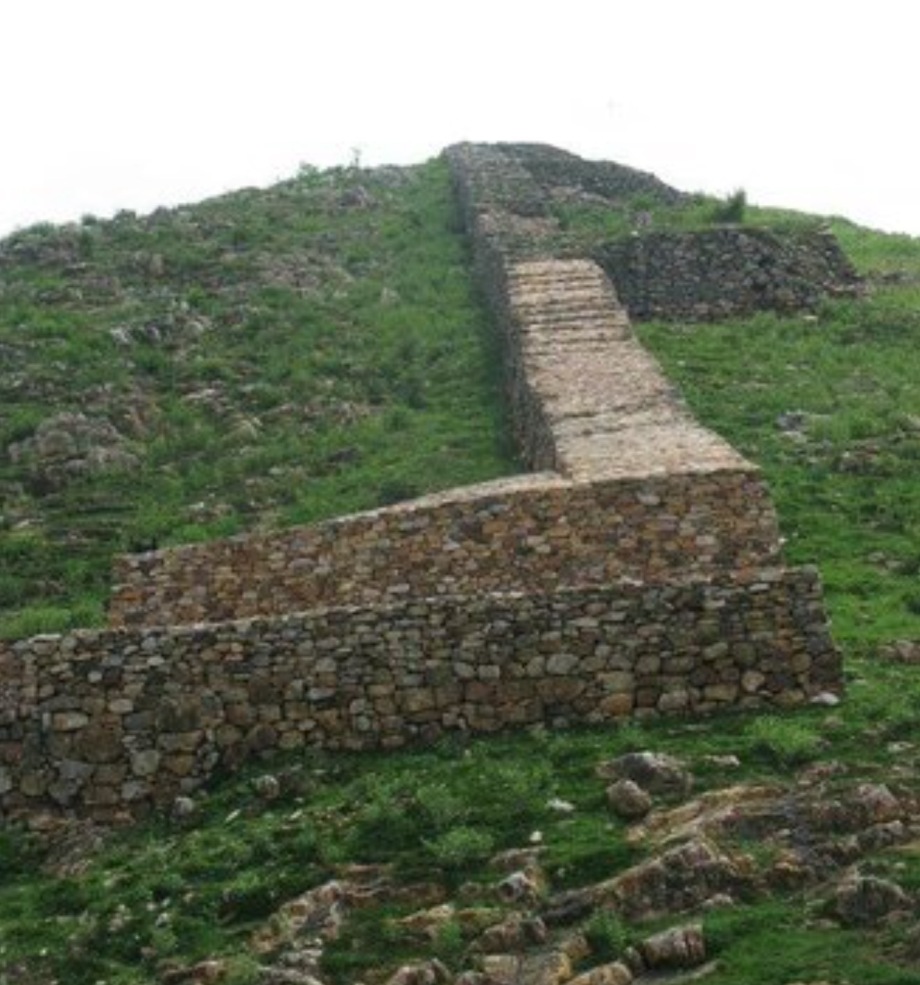

- Most mahajanapadas had a capital city, many of these were fortified. This means that huge walls of wood, brick or stone were built around them.

- Forts were probably built because people were afraid of attacks from other kings and needed protection.

- It is also likely that some rulers wanted to show how rich and powerful they were by building really large, tall and impressive walls around their cities.

- Also in this way, the land and the people living inside the fortified area could be controlled more easily by the king.

- Building such huge walls required a great deal of planning. Thousands, if not lakhs of bricks or stone had to be prepared. This in turn meant enormous labour, provided, possibly, by thousands of men, women and children. And resources had to be found for all of this.

- The new rajas now began maintaining armies. Soldiers were paid regular salaries and maintained by the king throughout the year. Some payments were probably made using punch marked coins.

- The sixteen mahajanapadas : The sixth century BCE is often regarded as a major turning point in early Indian history. It is an era associated with early states, cities, the growing use of iron, the development of coinage, etc. It also witnessed the growth of diverse systems of thought, including Buddhism and Jainism.

- Early Buddhist and Jaina texts mention, amongst other things, sixteen states known as mahajanapadas.

- Although the lists vary, some names such as Vajji, Magadha, Koshala, Kuru, Panchala, Gandhara and Avanti occur frequently. Clearly, these were amongst the most important mahajanapadas.

- While most mahajanapadas were ruled by kings, some, known as ganas or sanghas, were oligarchies, where power was shared by a number of men, often collectively called rajas.

- Both Mahavira and the Buddha belonged to such ganas.

- In some instances, as in the case of the Vajji sangha, the rajas probably controlled resources such as land collectively.

- Although their histories are often difficult to reconstruct due to the lack of sources, some of these states lasted for nearly a thousand years.

- Each mahajanapada had a capital city, which was often fortified. Maintaining these fortified cities as well as providing for incipient armies and bureaucracies required resources.

- From c. sixth century BCE onwards, Brahmanas began composing Sanskrit texts known as the Dharmasutras. These laid down norms for rulers (as well as for other social categories), who were ideally expected to be Kshatriyas. Rulers were advised to collect taxes and tribute from cultivators, traders and artisans.

- Were resources also procured from pastoralists and forest peoples? We do not really know. What we do know is that raids on neighbouring states were recognised as a legitimate means of acquiring wealth.

- Gradually, some states acquired standing armies and maintained regular bureaucracies. Others continued to depend on militia, recruited, more often than not, from the peasantry.

Taxes

- As the rulers of the mahajanapadas were building huge forts, maintaining big armies, they needed more resources. And they needed officials to collect these.

- So, instead of depending on occasional gifts brought by people, as in the case of the raja of the janapadas, they started collecting regular taxes.

- Taxes on crops were the most important. This was because most people were farmers. Usually, the tax was fixed at 1/6th of what was produced. This was known as bhaga or a share.

- There were taxes on crafts persons as well. These could have been in the form of labour. For example, a weaver or a smith may have had to work for a day every month for the king.

- Herders were also expected to pay taxes in the form of animals and animal produce.

- There were also taxes on goods that were bought and sold, through trade.

- And hunters and gatherers also had to provide forest produce to the raja.

Changes in agriculture

- There were two major changes in agriculture around this time. One was the growing use of iron ploughshares. This meant that heavy, clayey soil could be turned over better than with a wooden ploughshare, so that more grain could be produced. Second, people began transplanting paddy. This meant that instead of scattering seed on the ground, from which plants would sprout, saplings were grown and then planted in the fields. This led to increased production, as many more plants survived.

- However, it was back breaking work. Generally, slave men and women, (dasas and dasis) and landless agricultural labourers (kammakaras) had to do this work.

Inscriptions

- Inscriptions are writings engraved on hard surfaces such as stone, metal or pottery.

- They usually record the achievements, activities or ideas of those who commissioned them and include the exploits of kings, or donations made by women and men to religious institutions.

- Inscriptions are virtually permanent records, some of which carry dates. Others are dated on the basis of palaeography or styles of writing, with a fair amount of precision.

- The earliest inscriptions were in Prakrit, a name for languages used by ordinary people. Names of rulers such as Ajatasattu and Asoka, known from Prakrit texts and inscription. You will also find terms in languages such as Pali, Tamil and Sanskrit, which too were used to write inscriptions and texts.

- It is possible that people spoke in other languages as well, even though these were not used for writing.

- Epigraphy is the study of inscriptions.

- Oligarchy refers to a form of government where power is exercised by a group of men. The Roman Republic was an oligarchy in spite of its name.

Magadha

- Magadha became the most important mahajanapada in about two hundred years.

- Many rivers such as the Ganga and Son flowed through Magadha. This was important for transport, water supplies, making the land fertile.

- Parts of Magadha were forested. Elephants, which lived in the forest, could be captured and trained for the army. Forests also provided wood for building houses, carts and chariots.

- Besides, there were iron ore mines in the region that could be tapped to make strong tools and weapons.

- Magadha had two very powerful rulers, Bimbisara and Ajatasattu, who used all possible means to conquer other janapadas.

- Mahapadma Nanda was another important ruler. He extended his control up to the north-west part of the subcontinent.

- Rajagriha (present-day Rajgir) in Bihar was the capital of Magadha for several years.Later the capital was shifted to Pataliputra (present-day Patna).

- Between the sixth and the fourth centuries BCE, Magadha (in present-day Bihar) became the most powerful mahajanapada.

- Modern historians explain this development in a variety of ways: Magadha was a region where agriculture was especially productive. Besides, iron mines (in present-day Jharkhand) were accessible and provided resources for tools and weapons.

- Elephants, an important component of the army, were found in forests in the region.

- Also, the Ganga and its tributaries provided a means of cheap and convenient communication.

- However, early Buddhist and Jaina writers who wrote about Magadha attributed its power to the policies of individuals: ruthlessly ambitious kings of whom Bimbisara, Ajatasattu and Mahapadma Nanda are the best known, and their ministers, who helped implement their policies.

- Initially, Rajagaha (the Prakrit name for present- day Rajgir in Bihar) was the capital of Magadha. Interestingly, the old name means “house of the king”.

Fig.Fortification walls at Rajgir

- Rajagaha was a fortified settlement, located amongst hills. Later, in the fourth century BCE, the capital was shifted to Pataliputra, present-day Patna, commanding routes of communication along the Ganga.

- More than 2300 years ago, a ruler named Alexander, who lived in Macedonia in Europe, wanted to become a world conqueror. Of course, he didn’t conquer the world, but did conquer parts of Egypt and West Asia, and came to the Indian subcontinent, reaching up to the banks of the Beas. When he wanted to march further eastwards, his soldiers refused. They were scared, as they had heard that the rulers of India had vast armies of foot soldiers, chariots and elephants.

Vajji

- While Magadha became a powerful kingdom, Vajji, with its capital at Vaishali (Bihar), was under a different form of government, known as gana or sangha.

- In a gana or a sangha there were not one, but many rulers. Sometimes, even when thousands of men ruled together, each one was known as a raja. These rajas performed rituals together. They also met in assemblies, and decided what had to be done and how, through discussion and debate.

- For example, if they were attacked by an enemy, they met to discuss what should be done to meet the threat.

- However, women, dasas and kammakaras could not participate in these assemblies.

- Both the Buddha and Mahavira belonged to ganas or sanghas.

- Some of the most vivid descriptions of life in the sanghas can be found in Buddhist books.

- Gana Is used for a group that has many members.

- Sangha Means organisation or association.

- Rajas of powerful kingdoms tried to conquer the sanghas. Nevertheless, these lasted for a very long time, till about 1500 years ago, when the last of the ganas or sanghas were conquered by the Gupta rulers.

This is an account of the Vajjis from the Digha Nikaya, a famous Buddhist book, which contains some of the speeches of the Buddha. These were written down about 2300 years ago.

Ajatasattu and the Vajjis

Ajatasattu wanted to attack the Vajjis. He sent his minister named Vassakara to the Buddha to get his advice on the matter. The Buddha asked whether the Vajjis met frequently, in full assemblies. When he heard that they did, he replied that the Vajjis would continue to prosper as long as:

- They held full and frequent public assemblies.

- They met and acted together.

- They followed established rules.

- They respected, supported and listened to elders.

- Vajji women were not held by force or captured.

- Chaityas (local shrines) were maintained in both towns and villages.

- Wise saints who followed different beliefs were respected and allowed to enter and leave the country freely.

Buddha

- Siddhartha, also known as Gautama, the founder of Buddhism, was born about 2500 years ago.

- This was a time of rapid change in the lives of people. Some kings in the mahajanapadas were growing more powerful. New cities were developing, and life was changing in the villages as well.

- Many thinkers were trying to understand these changes in society. They also wanted to try and find out the true meaning of life.

- The Buddha belonged to a small gana known as the Sakya gana, and was a kshatriya.

- When he was a young man, he left the comforts of his home in search of knowledge. He wandered for several years, meeting and holding discussions with other thinkers.

- He finally decided to find his own path to realisation, and meditated for days on end under a peepal tree at Bodh Gaya in Bihar, where he attained enlightenment. After that, he was known as the Buddha or the Wise One.

- He then went to Sarnath, near Varanasi, where he taught for the first time.

- He spent the rest of his life travelling on foot, going from place to place, teaching people, till he passed away at Kusinara.

Fig.Stupa at Sarnath

- The Buddha taught that life is full of suffering and unhappiness. This is caused because we have cravings and desires (which often cannot be fulfilled). Sometimes, even if we get what we want, we are not satisfied, and want even more (or want other things).

- The Buddha described this as thirst or tanha. He taught that this constant craving could be removed by following moderation in everything.

- He also taught people to be kind, and to respect the lives of others, including animals.

- He believed that the results of our actions (called karma), whether good or bad, affect us both in this life and the next.

- The Buddha taught in the language of the ordinary people, Prakrit, so that everybody could understand his message.

- He also encouraged people to think for themselves rather than to simply accept what he said.

- Let us see how he did this.

The story of Kisagotami

- Once there was a woman named Kisagotami, whose son had died. She was so sad that she roamed through the streets of the city carrying the child with her, asking for help to bring him back to life.

- A kind man took her to the Buddha. The Buddha said: “Bring me a handful of mustard seeds, and I will bring your child back to life.” Kisagotami was overjoyed and started off at once, but the Buddha gently stopped her and added: “The seeds must come from the house of a family where nobody has died.”

- Kisagotami went from door to door, but wherever she went, she found out that someone or the other — father, mother, sister, brother, husband, wife, child, uncle, aunt, grandfather, grandmother — had died.

Upanishads

- Around the time that the Buddha was preaching and perhaps a little earlier, other thinkers also tried to find answers to difficult questions.

- Some of them wanted to know about life after death, others wanted to know why sacrifices should be performed.

- Many of these thinkers felt that there was something permanent in the universe that would last even after death. They described this as the atman or the individual soul and the brahman or the universal soul.

- They believed that ultimately, both the atman and the brahman were one.

- Many of their ideas were recorded in the Upanishads. These were part of the later Vedic texts.

- Upanishad literally means ‘approaching and sitting near’ and the texts contain conversations between teachers and students.

- Often, ideas were presented through simple dialogues.

- Most Upanishadic thinkers were men, especially brahmins and rajas. Occasionally, there is mention of women thinkers, such as Gargi, who was famous for her learning, and participated in debates held in royal courts.

- Poor people rarely took part in these discussions. One famous exception was Satyakama Jabala, who was named after his mother, the slave woman Jabali. He had a deep desire to learn about reality, was accepted as a student by a brahmin teacher named Gautama, and became one of the best-known thinkers of the time.

- Many of the ideas of the Upanishads were later developed by the famous thinker Shankaracharya.

Here is a dialogue based on a story from one of the most famous Upanishads, the Chhandogya Upanishad.

The wise beggar

Shaunaka and Abhipratarin were two sages who worshipped the universal soul. Once, as they sat down to eat, a beggar came and asked for some food. “We cannot spare anything for you,” Shaunaka said. “Learned sirs, whom do you worship?” the beggar asked. “The universal soul,” Abhipratarin replied. “Ah! It means that you know that the universal soul fills the entire world.” “Yes, yes. We know that.” The sages nodded. “If the universal soul fills the whole world, it fills me too. Who am I, but a part of the world?” the beggar asked. “You speak the truth, O young brahmin.” “Then, O sages, by not giving me food, you are actually denying food to the universal soul.” The sages realised the truth of what the beggar said, and shared their food with him.

Panini, the grammarian

This was also the time when other scholars were at work. One of the most famous was Panini, who prepared a grammar for Sanskrit.

He arranged the vowels and the consonants in a special order, and then used these to create formulae like those found in Algebra.

He used these to write down the rules of the language in short formulae (around 3000 of them!).

Jainism

- The word Jaina comes from the term Jina, meaning conqueror. The most famous thinker of the Jainas, Vardhamana Mahavira, also spread his message around this time, i.e. 2500 years ago.

- He was a kshatriya prince of the Lichchhavis, a group that was part of the Vajji sangha

- At the age of thirty, he left home and went to live in a forest. For twelve years he led a hard and lonely life, at the end of which he attained enlightenment.

- He taught a simple doctrine: men and women who wished to know the truth must leave their homes. They must follow very strictly the rules of ahimsa, which means not hurting or killing living beings.

- “All beings,” said Mahavira “long to live. To all things life is dear.”

- Ordinary people could understand the teachings of Mahavira and his followers, because they used Prakrit.

- There were several forms of Prakrit, used in different parts of the country, and named after the regions in which they were used. For example, the Prakrit spoken in Magadha was known as Magadhi.

- Followers of Mahavira, who were known as Jainas, had to lead very simple lives, begging for food. They had to be absolutely honest, and were especially asked not to steal. Also, they had to observe celibacy. And men had to give up everything, including their clothes.

- It was very difficult for most men and women to follow these strict rules. Nevertheless, thousands left their homes to learn and teach this new way of life.

- Many more remained behind and supported those who became monks and nuns, providing them with food.

- Jainism was supported mainly by traders. Farmers, who had to kill insects to protect their crops, found it more difficult to follow the rules.

- Over hundreds of years, Jainism spread to different parts of north India, and to Gujarat, Tamil Nadu and Karnataka.

- The teachings of Mahavira and his followers were transmitted orally for several centuries. They were written down in the form in which they are presently available at a place called Valabhi, in Gujarat, about 1500 years ago

The sangha

- Both the Mahavira and the Buddha felt that only those who left their homes could gain true knowledge.

- They arranged for them to stay together in the sangha, an association of those who left their homes.

- The rules made for the Buddhist sangha were written down in a book called the Vinaya Pitaka.

- From this we know that there were separate branches for men and women. All men could join the sangha. However, children had to take the permission of their parents and slaves that of their masters. Those who worked for the king had to take his permission and debtors that of creditors. Women had to take their husbands’ permission.

- Men and women who joined the sangha led simple lives. They meditated for most of the time, and went to cities and villages to beg for food during fixed hours. That is why they were known as bhikkhus (the Prakrit word for beggar) and bhikkhunis.

- They taught others, and helped one another. They also held meetings to settle any quarrels that took place within the sangha.

- Those who joined the sangha included brahmins, kshatriyas, merchants, labourers, barbers, courtesans and slaves.

- Many of them wrote down the teachings of the Buddha. Some of them also composed beautiful poems, describing their life in the sangha.

Monasteries

- To begin with, both Jaina and Buddhist monks went from place to place throughout the year, teaching people.

- The only time they stayed in one place was during the rainy season, when it was very difficult to travel.

- Then, their supporters built temporary shelters for them in gardens, or they lived in natural caves in hilly areas.

- As time went on, many supporters of the monks and nuns, and they themselves, felt the need for more permanent shelters and so monasteries were built. These were known as viharas.

- The earliest viharas were made of wood, and then of brick. Some were even in caves that were dug out in hills, especially in western India.

- Very often, the land on which the vihara was built was donated by a rich merchant or a landowner, or the king. The local people came with gifts of food, clothing and medicines for the monks and nuns. In return, they taught the people.

- Over the centuries, Buddhism spread to many parts of the subcontinent and beyond. A Buddhist text tells us: Just as the waters of rivers lose their names and separateness when they flow into the mighty ocean, so are varna and ranks and family forgotten when the followers of the Buddha join the order of monks.

The system of ashramas

- Around the time when Jainism and Buddhism were becoming popular, brahmins developed the system of ashramas.

- Here, the word ashrama does not mean a place where people live and meditate. It is used instead for a stage of life. Four ashramas were recognised: brahmacharya, grihastha, vanaprastha and samnyasa.

- Brahmin, kshatriya and vaishya men were expected to lead simple lives and study the Vedas during the early years of their life (brahmacharya). Then they had to marry and live as householders (grihastha). Then they had to live in the forest and meditate (vanaprastha). Finally, they had to give up everything and become samnyasins.

- The system of ashramas allowed men to spend some part of their lives in meditation.

- Generally, women were not allowed to study the Vedas, and they had to follow the ashramas chosen by their husbands.